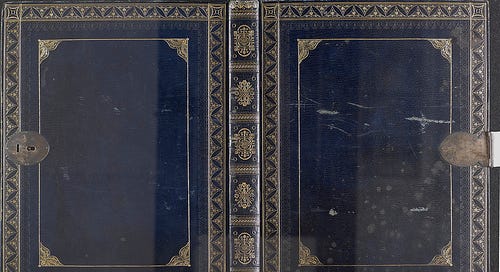

Lady Caroline Lamb's Heart-Break Notebook

"I will kneel & be torn from your feet before I will give you up…"

I’ve wanted to write about this particular notebook since I first saw it in 2010 at the National Library of Scotland. It’s just so shocking, so dramatic, so illicit! I figured, what better time to share a notebook that chronicles a disastrous romance than Valentine’s Day?

Here’s the context:

Lady Caroline Lamb (1785-1827) was a socialite. Wealthy and be…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Noted to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.