Frederick Douglass's Liberation Notes

"…I instinctively understood the pathway from slavery to freedom."

Freedom cannot exist without education.

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) absorbed this lesson when, as an enslaved child, he learned to read and write in secret. Education, he discovered, was incompatible with slavery. Once he could recognize the letters of the alphabet, Douglass wrote,

…I instinctively understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.1

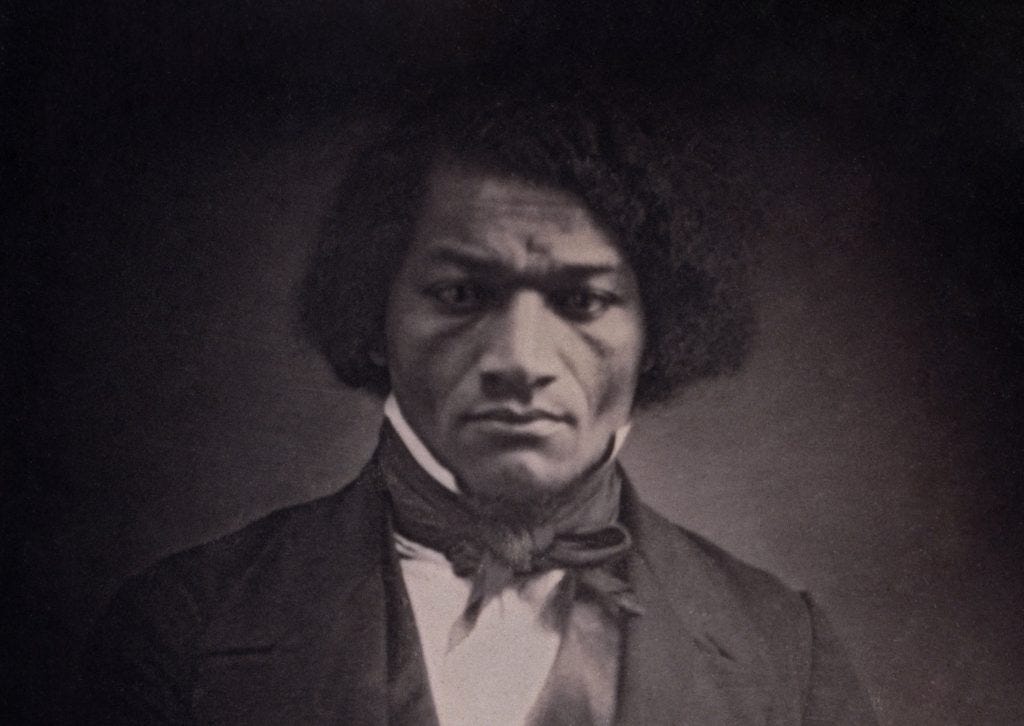

After he escaped, Douglass fought to abolish slavery by educating Americans and the world at large. Through his autobiographies and worldwide lecture tour, through his many photographs and searing rhetoric, Douglass taught the world about his own basic humanity and, as such, his right to freedom.

Just as abolishing slavery depended on education, so did the following century’s civil rights movement. In fact, I can’t think of a single fight for equality that did not depend on education. So today, as we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr.—a great student and teacher—let us turn to a man who made King’s fight possible: The remarkable, inimitable Frederick Douglass.

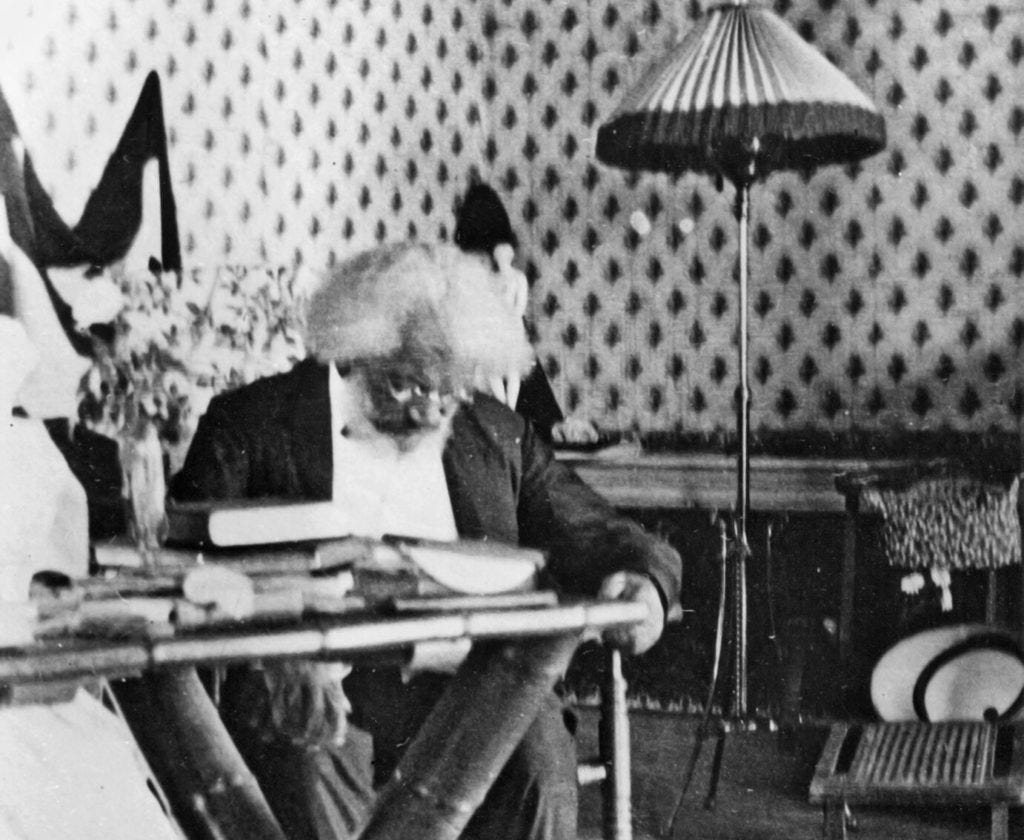

In the nineteenth century, no American was photographed more than Frederick Douglass. No American traveled as widely as he did (with the possible exception of Mark Twain). And nobody represented the stark contrasts of the American experience quite as powerfully as Douglass.2

All of it began with literacy.

Douglass’s Early Literacy Notes

As with any history of slavery, the archive is filled with irrecoverable silences. The scholar Saidiya Hartman writes poignantly:

The irreparable violence of the Atlantic slave trade resides precisely in all the stories that we cannot know and that will never be recovered.3

While we don’t have Douglass’s earliest notes, he detailed how he used note-taking to teach himself to write. Sophia Auld, his master’s wife, taught Douglass his letters, but she was quickly reprimanded when her husband Hugh Auld learned of the lesson.

This only ignited Douglass’s passion for education—he would have to continue it himself. Douglass learned to write by borrowing the copy books of the Auld’s son (“Master Tommy”) and transcribing the same phrases himself in the blank spaces.

When my mistress left me in charge of the house, I had a grand time; I got Master Tommy’s copy books and a pen and ink, and, in the ample spaces between the lines, I wrote other lines, as nearly like his as possible. The process was a tedious one, and I ran the risk of getting a flogging for marring the highly prized copy books of the oldest son.4

Additionally, while working part-time on the docks in Maryland, Douglass befriended white boys who continued teaching him.

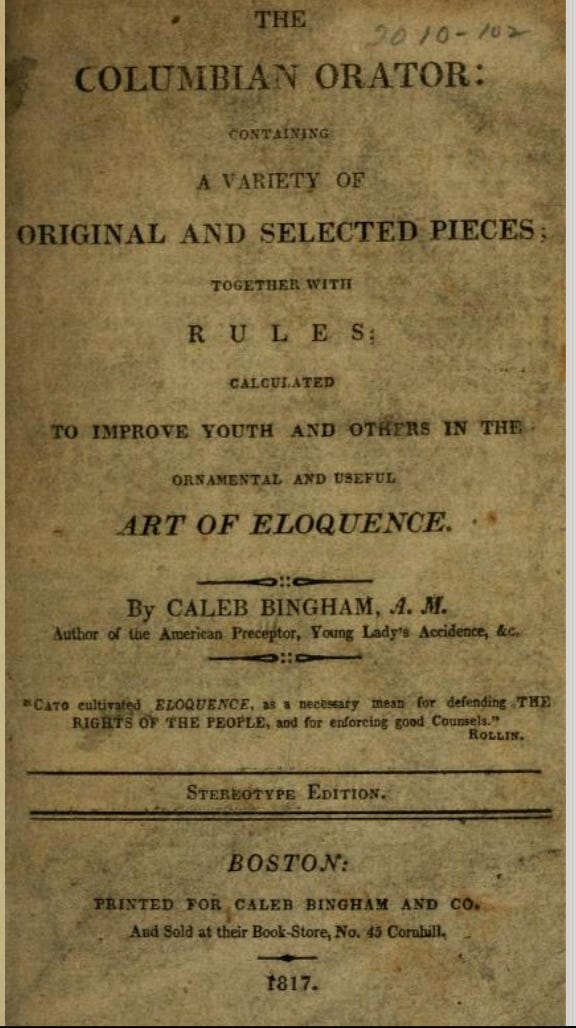

When Douglass made enough money from the docks, he bought The Columbian Orator—a popular textbook his white friends used. This book taught elocution with an abolitionist bent, and it meant so much to the young Douglass that when he escaped, he carried it north with him.

Douglass knew that his pen and his voice were his most powerful political tools. And throughout his life he worked tirelessly to polish both.

Douglass’s Autobiographical Notes

Douglass maintained a deep desire to understand his own history—to understand where he came from. As he wrote,

Genealogical trees do not flourish among slaves.5

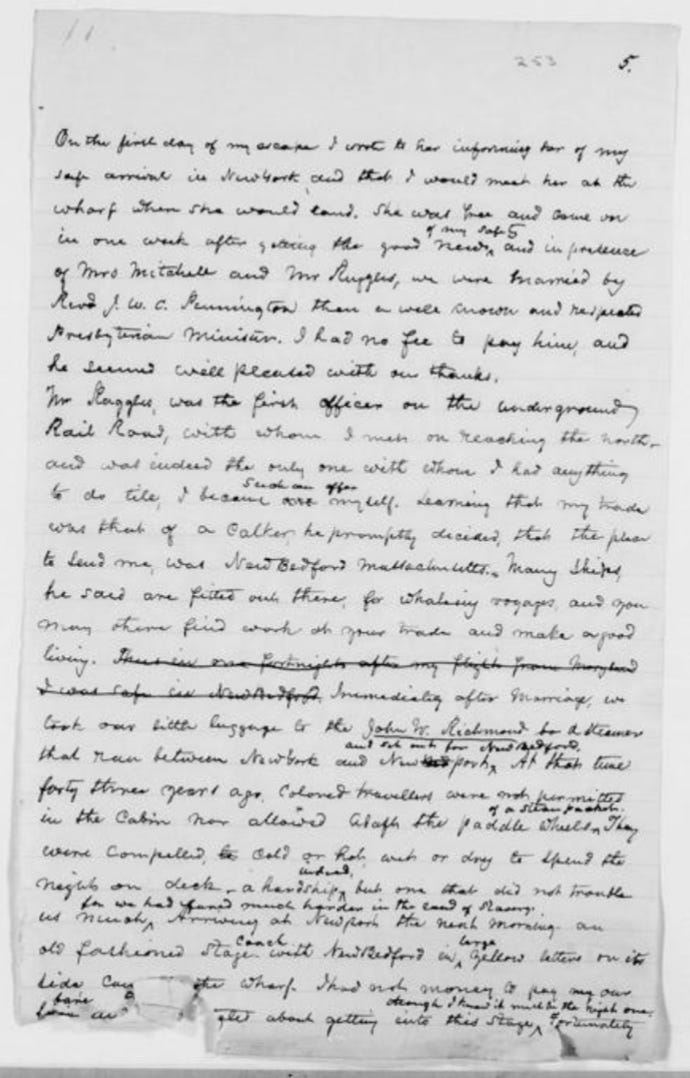

Douglass would tell the story of his life three different times in his three autobiographies. Each time, he added more information. Here is a draft for his third autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which contains a poignant description of his wife, Anna, a free Black woman who, according to family legend, sold her feather bed so that Douglass had money for his escape. In this draft, he writes:

On the first day of my escape I wrote to her [his fiancé, Anna Murray] informing her of my safe arrival in New York and that I would meet her at the wharf when she would land. She was free and came on in one week after getting the good news and in presence of Mrs. Mitchell and Mrs. Ruggles we were married…

The drafts of his autobiographies demonstrate how Douglass worked tirelessly to narrate his own life.

It was a skill he honed on the pulpit, where his dazzling lecture career began. In his first speeches, he dispassionately narrated the facts of his life before building to a heated take-down of slavery.6

Douglass’s Piles of Paper

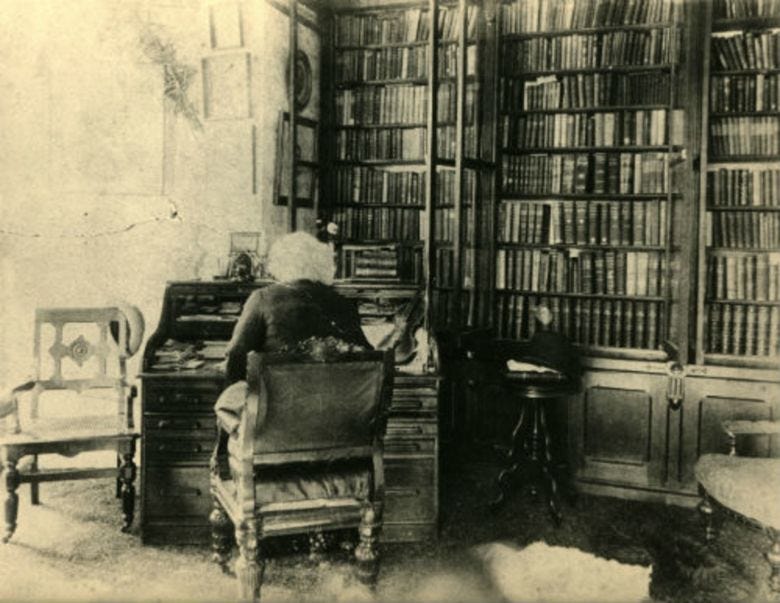

Much of Douglass’s archive consists of what the Library of Congress calls “Subject Files.” These were piles of paper that Douglass had in his library at the time of his death.

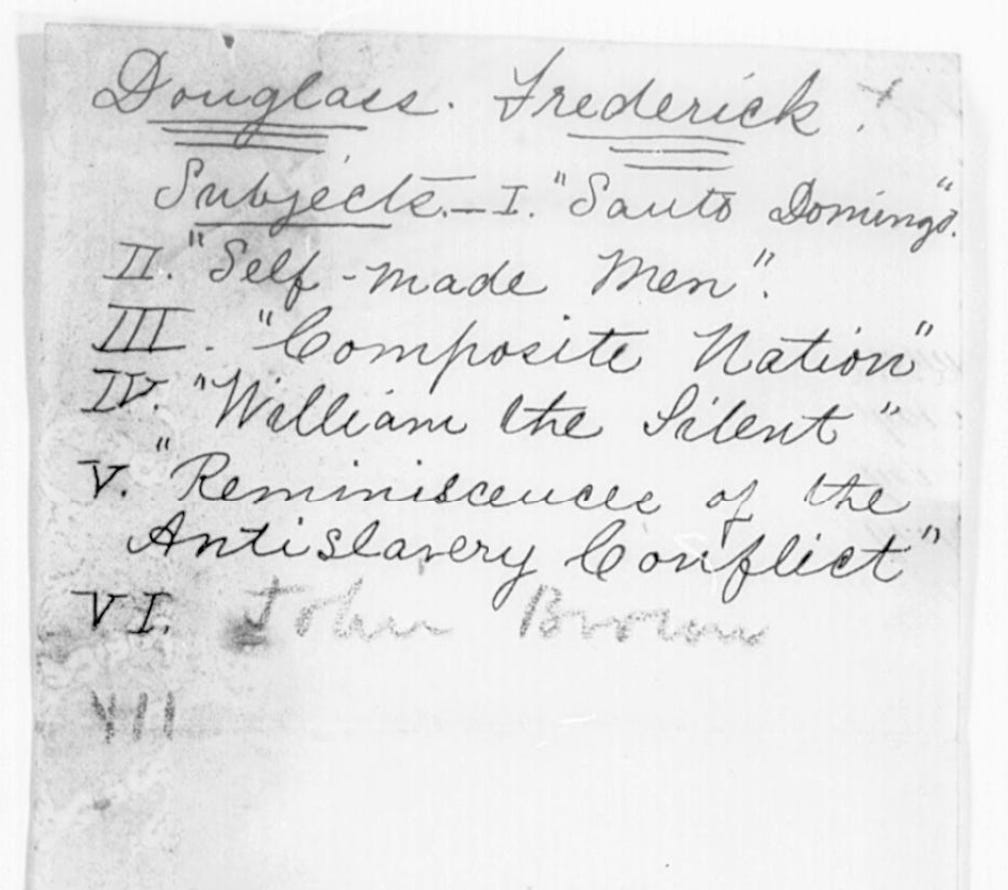

Included in these files is the following list of speech titles in Douglass’s own hand:

Douglass, Frederick

Subjects I. “Santo Domingo”

II. “Self-Made Men”

III. Composite Nation

IV. “William the Silent”

V. “Reminiscence of the Antislavery Conflict”

VI. John Brown

VII

When Douglass began his lecturing career, he often went to the lectern with only a list of subjects. As a friend later recalled:

On a table near him was a leaf of paper on which were scrawled perhaps two-dozen words. “What is this?” I said. “That,” he replied with a laugh, “is my speech.”7

As Douglass matured as a speaker, he often brought books and newspaper clippings to the lectern along with his outline. He would read quotes from these clippings to bolster his points.

You can see the “subject files” with many of Douglass’s clippings at the Library of Congress website.

Douglass avidly collected newspaper clippings and maintained several scrapbooks. He was passionate about new technologies as liberatory tools—especially photography.

Frederick Douglass’s Photographs

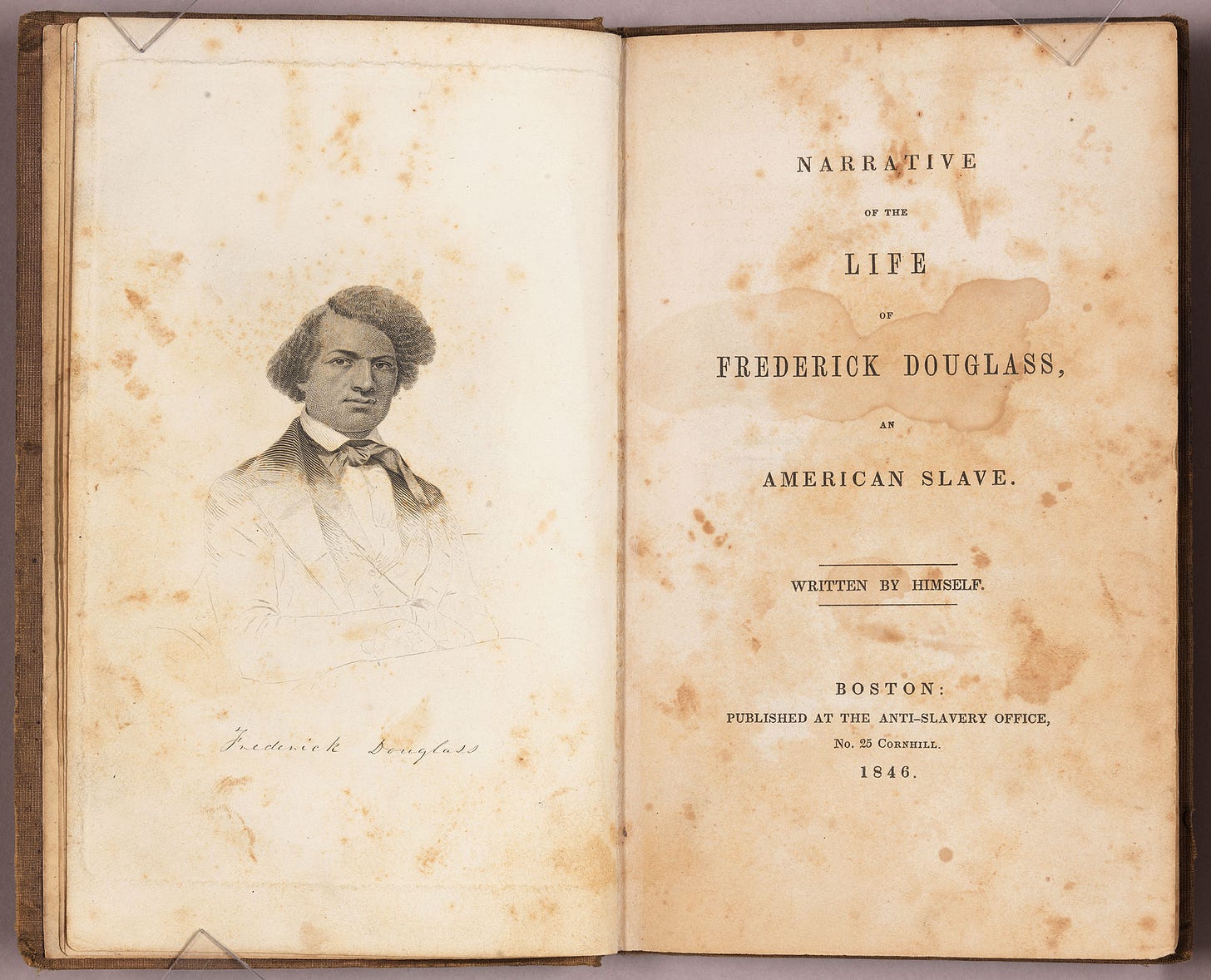

When Douglass published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, rumors swirled around the book. People couldn’t believe that a Black person wrote so beautifully.

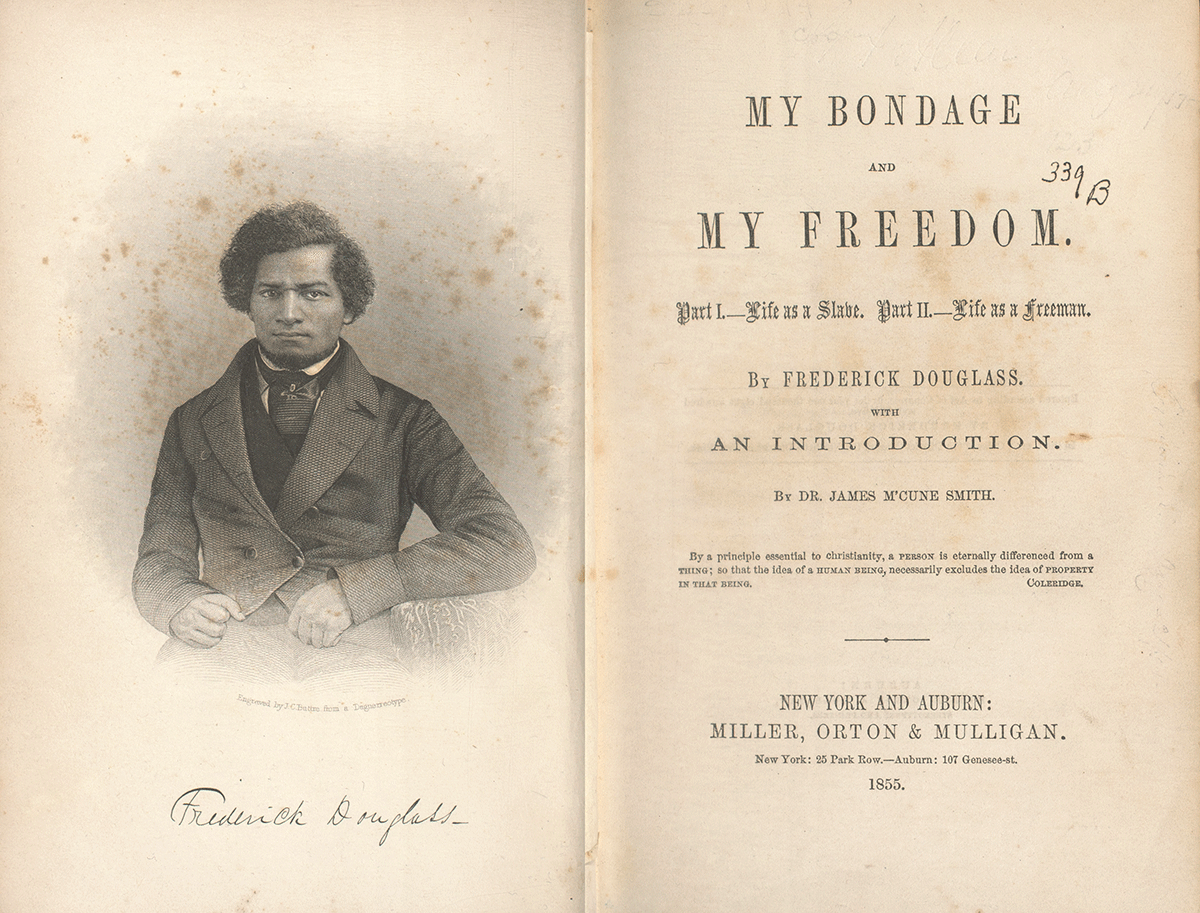

In response, Douglass ensured that the second edition contained a daguerreotype portrait of the author along with his signature—guaranteeing the story’s authenticity.

Douglass’s second autobiography contained another photograph and signature—both matured over the intervening decade.

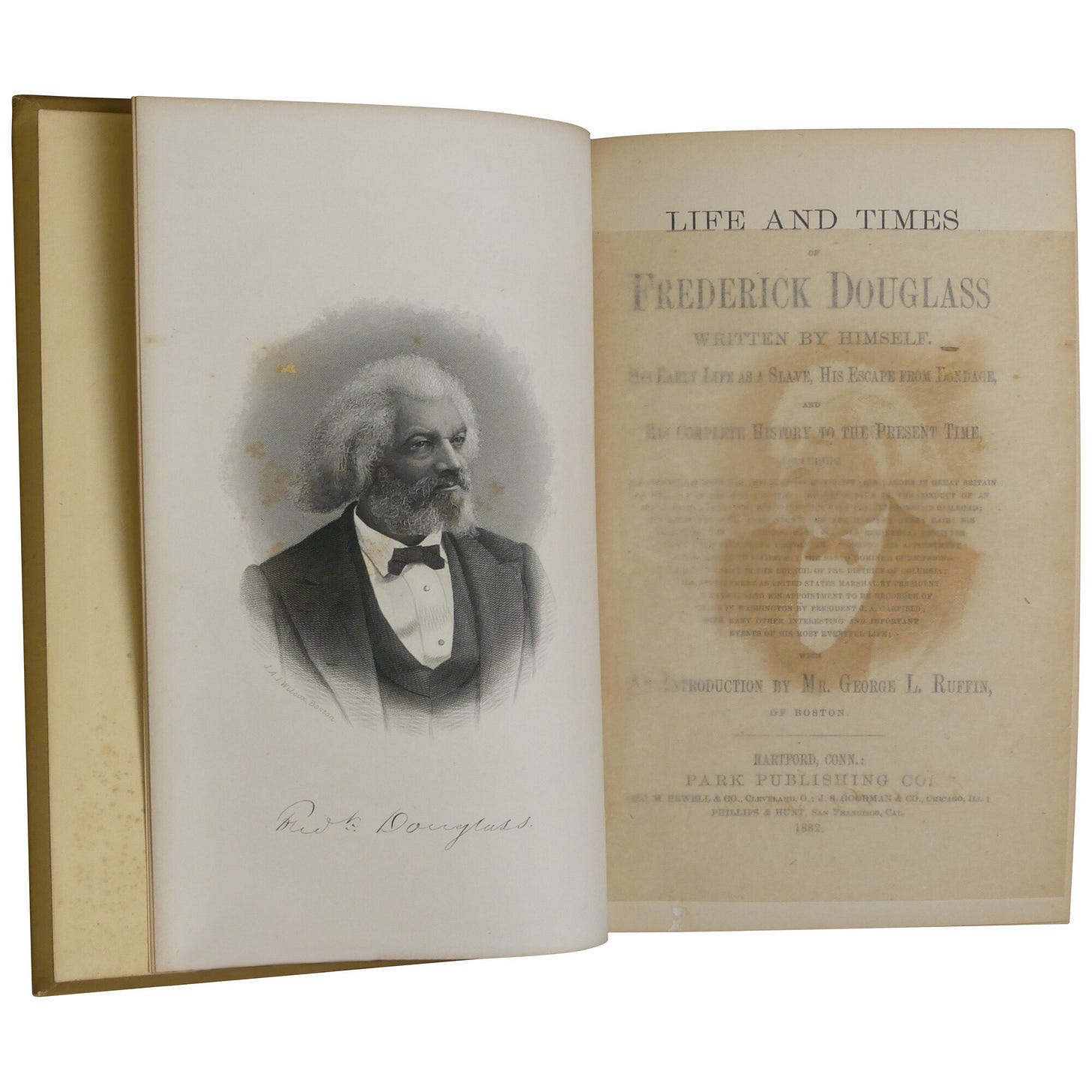

And, again in his last Autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

Douglass felt that photographs offered incontrovertible evidence against the hateful stereotypes that haunted Black Americans. (In this way, Douglass anticipated W.E.B. Du Bois’s photographs and data visualizations for the 1900 Paris Exposition.)

Given his interest in documentary evidence, Douglass also kept scrapbooks to collect newspaper cuttings related to his projects. It was a way to keep track of public opinion.

For example, in 1871, Douglass served as U.S. Commissioner to the Dominican Republic (called Santo Domingo at the time). President Grant wanted to annex the country and sent Douglass to learn if such a scheme would be successful.

During this time, Douglass cut out many newspaper articles about the Dominican Republic and neighboring Haiti. Amusingly, Douglass wrote the following alongside a portrait of Haiti’s President Hyppolite:

about as much like Pres. Hyppolite as like Pres. Harrison.

Douglass also saved articles related to himself, but his greatest document from his travels were his diaries.

Douglass’s Diaries

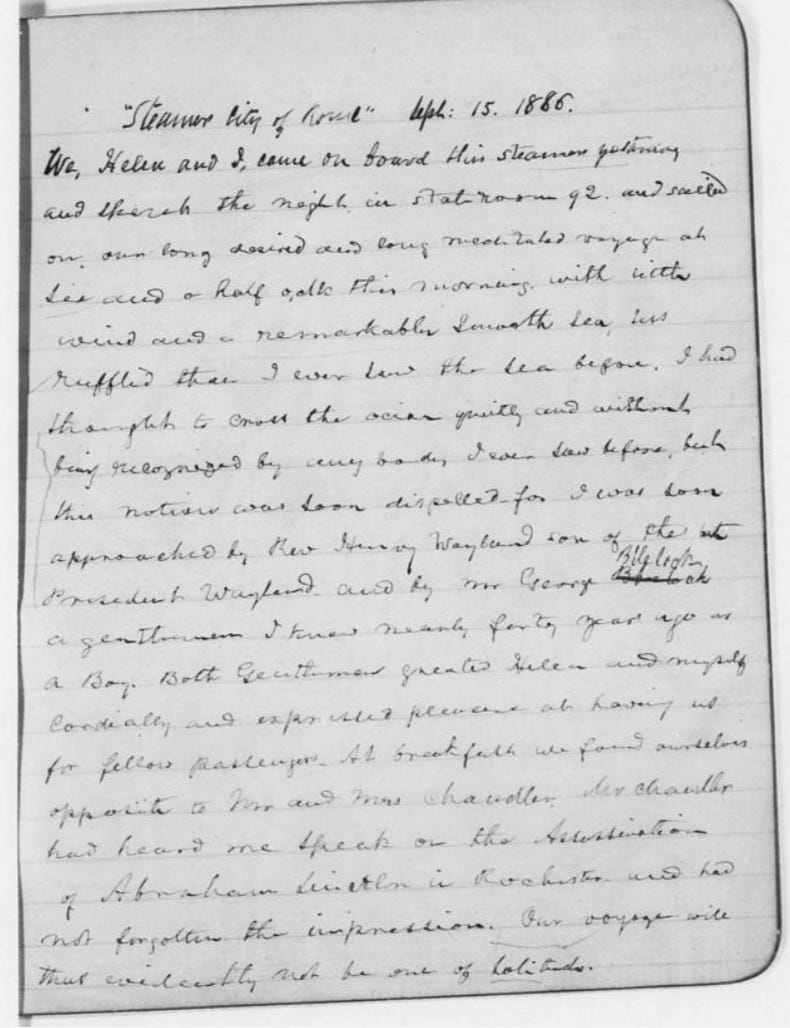

Douglass left behind two diaries —both kept while traveling internationally.

While in Santo Domingo, he carried a small pocket notebook and recorded the names of people he met. He visited Columbus’s house and saw where the first enslaved Africans were sold.

Later, while traveling through Europe and Africa, he kept a more robust account of his days so he could share his adventures with his son when he returned. By this time, his wife Anna had died, and he had remarried. His new wife, a white abolitionist named Helen, accompanied him on this trip.

With the conclusion of his travels, Douglass put his diary away. He took it out six years later, just a year before his death.

What was so important that it required a return to this diary? He had learned information about his former owners—the Aulds: Sophia who taught him to recognize letters and Hugh who forbade it.

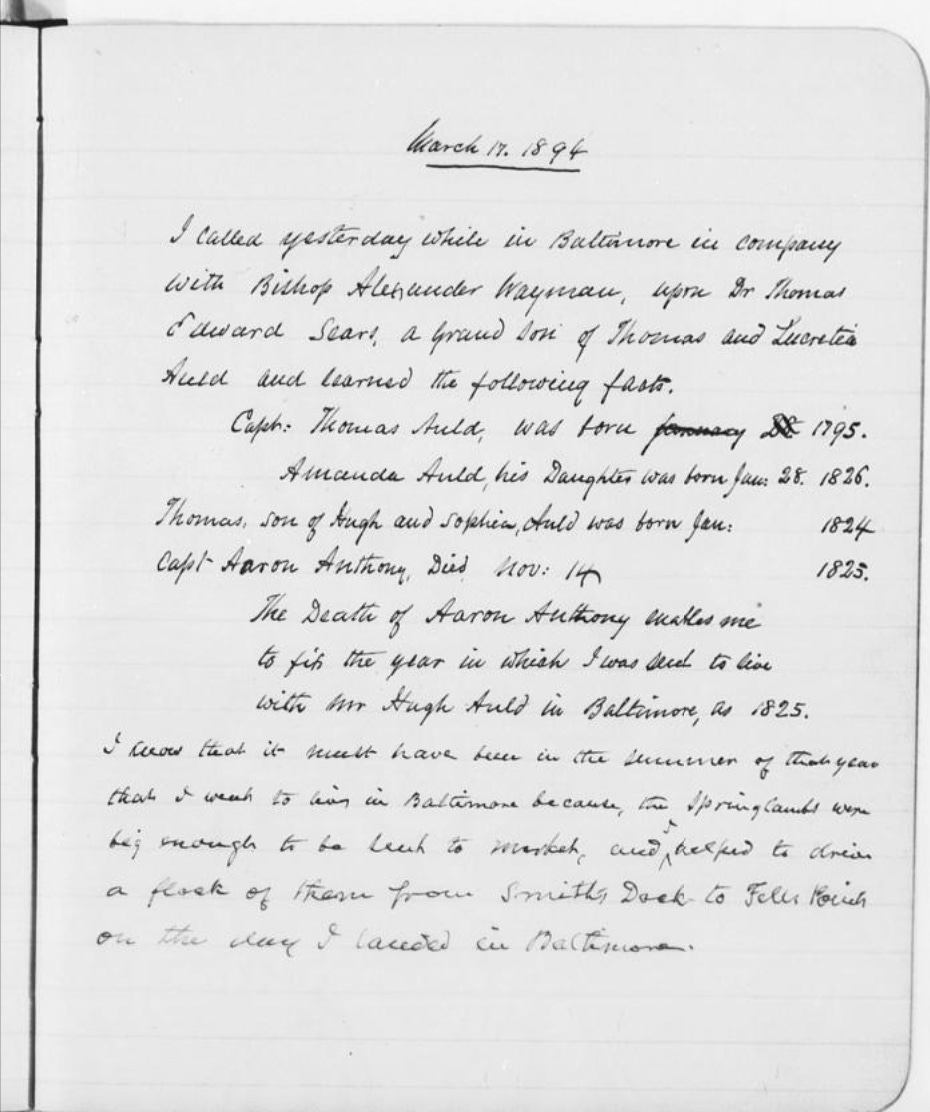

This final entry reads:

March 17 1894

I called yesterday while in Baltimore with Bishop Alexander Wayman, upon Dr. Thomas Edward Sears, a grand son of Thomas and Lucretia Auld and learned the following facts.

Capt Thomas Auld was born 1795

Amanda Auld, his daughter was born Jan 28 1826.

Thomas, son of Hugh and Sophia Auld was born Jan: 1824

Capt. Aaron Anthony, Died Nov: 14

The death of Aaron Anthony makes me

to fix the year in which I was sent to live

with Mr. Hugh Auld in Baltimore as 1825

I know that it must have been in the summer of that year that I went to live in Baltimore because the Spring lambs were big enough to be sent to market and I helped to drive a flock of them from Smith’s Dock to Fells Point on the day I landed in Baltimore.

Even with all the fame and prestige Douglass accrued as a celebrity, lecturer, bestselling author, and advisor to four presidents, he returned, always, to his beginnings. He wanted to know the dates of his life—dates that had been withheld from him.8

As Douglass understood, education begins with the self. First, we must know ourselves. Then, we can know our surroundings.

Because education is the most powerful political tool—in the nineteenth century and today—it behoves us to learn about our own stories. To learn about ourselves and then to learn how we fit into the waves of history.9

As Douglass teaches us, without education, there is no freedom.

Notes on Douglass’s Notes

Learn about yourself first: The diary and autobiography are designed for self-reflection and investigation. Record the facts of your life and all the information you can gather about your family. Because history and social situations are so vast and complex, it is helpful to understand oneself—and one’s family—before understanding how you fit into the broader historical narrative.

Great speeches often come from a small outline: While Douglass labored over drafts of his autobiographies, he couldn’t do the same with his speeches. Instead, he wrote out a handful of points he wanted to address. Famously, MLK Jr. ad libbed the“I have a dream” section of his speech at Mahalia Jackson’s encouragement. And, one of the first posts I ever wrote for Noted focused on James Baldwin and the notes he brought to the podium during his debate with Buckley. Much like Douglass, Baldwin had little written down—simply a series of points which he meandered away from during his speech.

Become an autodidact: Douglass never had a formal education; however, he seized upon books and companions who could teach him. He took his education into his own hands. And he never stopped learning.

Yours in Note-Taking,

P.S.

Paid Subscribers, look out for a post on Douglass’s social notes next Monday.

Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Park Publishing Company, 1882, p. 97.

In a talk titled “The Nature of Slavery,” Douglass explained,

It is perfectly well understood at the south, that to educate a slave is to make him discontented with slavery, and to invest him with a power which shall open to him the treasures of freedom; and since the object of the slaveholder is to maintain complete authority over his slave, his constant vigilance is exercised to prevent everything which militates against, or endangers, the stability of his authority. Education being among the menacing influences, and, perhaps, the most dangerous, is, therefore, the most cautiously guarded against. [My emphasis.]

Included in the 1855 edition of My Bondage and My Freedom.

“Venus in Two Acts” Small Axe, Number 26, 2008. See also Hartman’s gorgeous book, Lose Your Mothe A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (2007). Macmillan, 2007.

For more on a more tragic history of note-taking, see Caitlin Rosenthal’s Accounting for Slavery.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. New York and Auburn, Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855.

Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, p. 25.

See Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. Simon and Schuster, 2020, Chapter 6.

Recorded by James Monroe, a Connecticut abolitionist and quoted in Douglass, Frederick. The Frederick Douglass Papers: Volume 1, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, 1841-1846. Edited by Professor John W. Blassingame, Yale University Press, 1979.

For more, see Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s “Frederick Douglass and the Language of The Self” in The Yale Review.

I’m alluding to my favorite line from Douglass’s speech “Self-Made Men”:

I believe in individuality, but individuals are, to the mass, like waves to the ocean. The highest order of genius is as dependent as is the lowest. It, like the loftiest waves of the sea, derives its power and greatness from the grandeur and vastness of the ocean of which it forms a part. We differ as the waves, but are one as the sea.

I read his autobiography in college - such an inspiring, uniquely American story!

Nice work, Jillian! An inspiring chronicle on how to re-create a life.