Pictograms from the Aztec's Ancient Notes

"The story of Indian Mexico must be written with soft chalk, easily erased and corrected."

Much of what we know about ancient civilizations comes from the notes they took—their records of historical events, calendars, and mythology. While these notes might look different from our own, they are motivated by the same impulse: to save information from the ravages of memory and time.

Decades ago, I fell in love with Aztec (and Mayan)1 systems of writing which relied on graphic symbols to represent information. Their notes feel like a giant puzzle or a portal to another world!

If you’ve seen Frida Kahlo’s paintings or those of her husband, Diego Rivera, you likely have seen representations of Aztec culture and writing.

When it comes to ancient civilizations, so much remains unknowable. We depend on the records that remain—often those preserved by people belonging to other civilizations. We can only hope for an incomplete picture of empires like that of the Aztecs. And that picture often changes based on new scholarly research. As the scholar, Pablo Martínez del Río said:

The story of Indian Mexico must be written with soft chalk, easily erased and corrected.

Only a dozen ancient books from indigenous groups of the Americas exist from before contact with Europeans. In the case of the Aztecs (and Mayans), Spaniards systematically destroyed nearly all texts by burning libraries and archives in an attempt to squash pagan ideas.2 However, the Spaniards encouraged the Aztecs to keep writing so they could learn about Aztec culture and, more to the point, their natural resources (gold!). Thus, we find many Aztec manuscripts annotated in Spanish—a fascinating inter-weaving of cultures and intentions.

Some vocabulary you’ll need for this post: a codex is the scholarly name for an ancient book; codices is the plural form.

Let’s explore some of the most fascinating Aztec pictograms!

1) Place Names: Aztlán

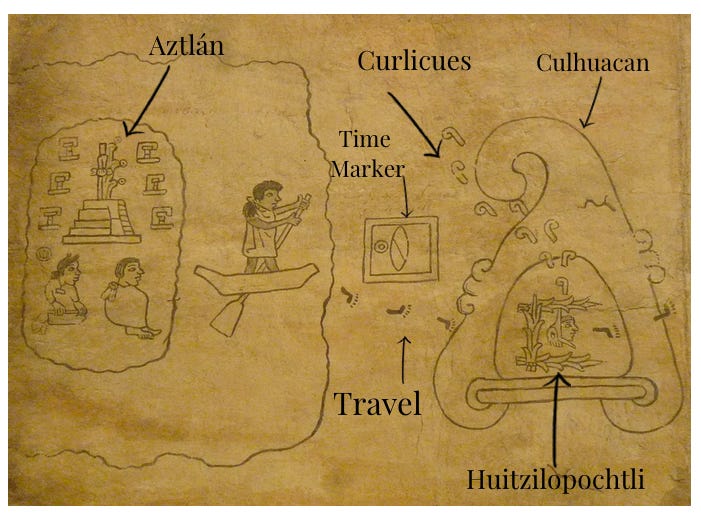

Many of the Aztec notes detail the group’s journey from the land of Aztlán to Mexica/Tenochtitlan, or what is currently Mexico City. Scholars debate whether Aztlán ever existed or if it was only a mythological place. Regardless, it was central to the Aztec’s conception of themselves.3

Traditionally, Aztlán is represented as an island of reeds surrounded by water as it is in the following image from Codex Boturini—one of the earliest surviving Aztec codices. Note the little footprints signifying movement away from Aztlán towards Culhuacan, a city-state located in the Valley of Mexico. The god, Huitzilopchtli (represented as a bird), is depicted on Culhuacan offering advice to the travelers.

I’ve added arrows and names as a guide to images throughout this post:

Let’s dig deeper and take a look at some of the glyphs (pictograms) depicted in this image as well as other manuscripts left behind by the Aztecs.

2) Curlicues

The color and direction of the curlicues signify their meaning. For the most part, curlicues reference speech marks. Curlicues colored blue or red (after precious stones) refer to words spoken by important people. If they are grey, however, they usually symbolize fire.

Throughout most of these manuscripts, a Spanish scribe translates the Aztec pictographs into their European alphabet.4 For example, consider the Spaniard’s note (written on the figure), naming him Emperor Axayacatl. But Aztecs would recognize Emperor Axayacatl by the pictogram representing his name floating above his head. His name literally means “water face,” so he is depicted with water alongside his face.5

3) Names

As we’ve seen, Aztecs represented names of people as well as names of locations with glyphs. When combined, the place name and a personal name can help tell a more complex story.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Noted to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.