Re-Noted: James Baldwin's Doodles

"You want to write a sentence as clean as a bone. That is the goal."

I have loved Baldwin since I read the first few lines of The Fire Next Time, a letter to his nephew (also named James). In it, Baldwin offers a deeply personal account of what it meant to be a Black man in 1960s America.

Dear James,

I have begun this letter five times and torn it up five times. I keep seeing your face, which is also the face of your father and my brother. Like him, you are tough, dark, vulnerable, moody—with a very definite tendency to sound truculent because you want no one to think you are soft. You may be like your grandfather in this, I don’t know, but certainly both you and your father resemble him very much physically. Well, he is dead, he never saw you, and he had a terrible life; he was defeated long before he died because, at the bottom of his heart, he really believed what white people said about him…

At this point, if you want to abandon my post to read the rest of The Fire Next Time, I wouldn’t blame you. But I hope you’ll stick around to learn a bit more about Baldwin’s note-taking practices.

Thanks to Raoul Peck’s excellent documentary, I am Not Your Negro, James Baldwin has become more widely known as an important civil rights leader and literary genius — but he’s still not as well know as he should be.

Last year, I visited the Schomburg Library to see Baldwin’s papers. The executors of Baldwin’s estate have tight regulations. For that reason, I wasn’t allowed to take photographs in the archive, but I still think I can give you a sense of his notes with the help of some images that are already online.

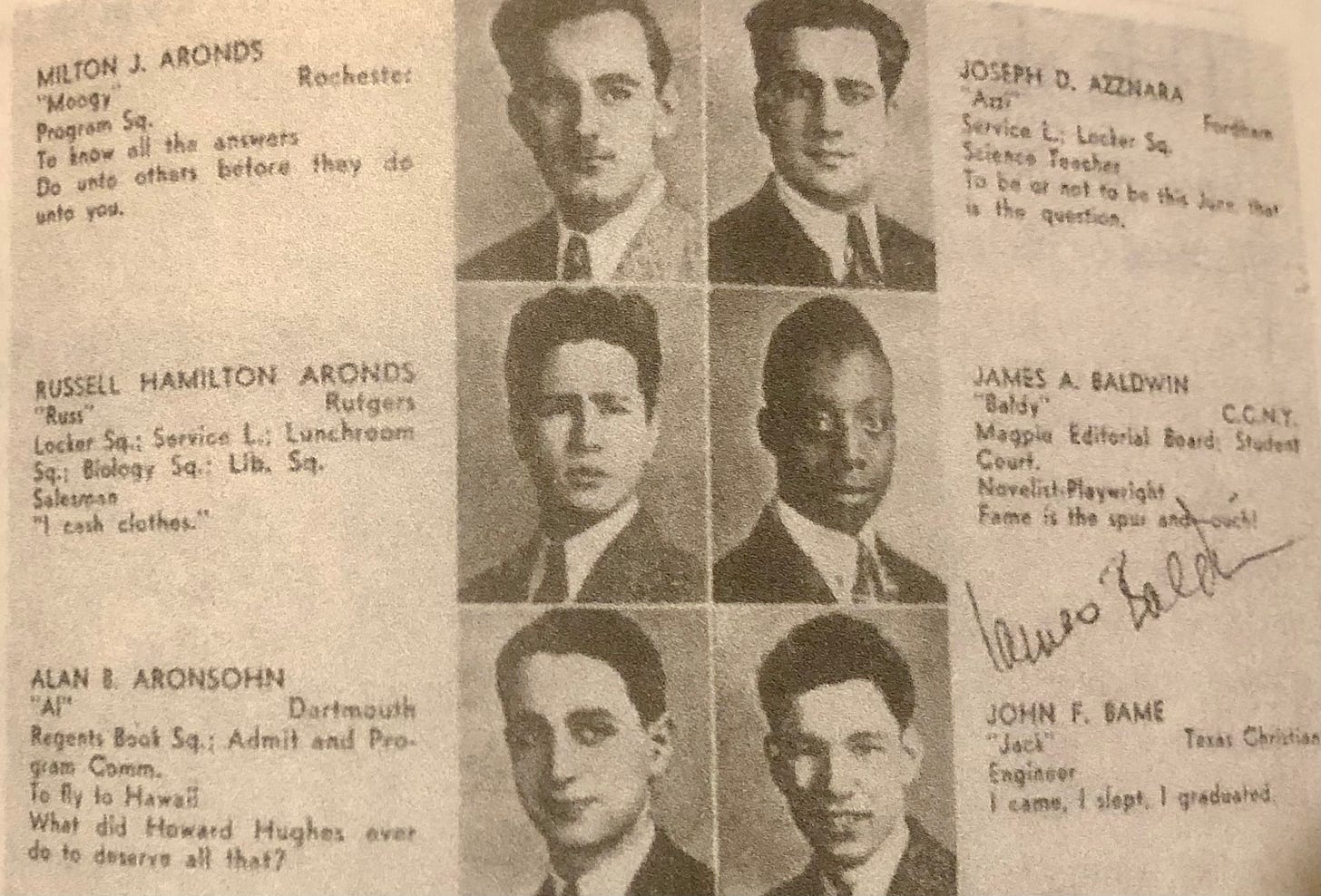

James Baldwin was brilliant and focused from a young age. When he graduated from high school, he listed his ambitions as “Novelist, Playwright.” He had plans to attend CUNY’s City College of New York (CCNY), but, being the eldest of 9 children, he took a job to support his family instead.

Because he worked during the day, Baldwin wrote at night. He continued this habit throughout his life. He explains,

I start working when everyone has gone to bed. I’ve had to do that ever since I was young — I had to wait until the kids were asleep. And then I was working at various jobs during the day. I’ve always had to write at night. But now that I’m established I do it because I’m alone at night.1

In 1948, Baldwin departed for France, where he would live for most of his life. He felt he needed “distance from the racial realities at home, so he could become the writer he wanted to be.”2 So Baldwin arrived in post-war Paris with his last $50. He stayed in decrepit hotel rooms and did his writing in cafes.

As soon as I was out of bed, I hopefully took notebook and fountain pen off to the upstairs room of the [Café de] Flore, where I consumed rather a lot of coffee and, as evening approached, rather a lot of alcohol.3

The A,B,C,D Outline

The most consistent organizational scheme that I saw in Baldwin’s notes is what I’ll call, for lack of a better name, the A,B,C,D outline. By this I mean simply that Baldwin listed out ideas with the letters of the alphabet, as he does on the following notepad from the Sheraton Tacoma Hotel. Here, he writes about Malcolm X—a man he had a complex relationship with.4 After Malcolm's assassination, Baldwin had plans to write a play based on The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

MX’s questionTo Be A Citizen Of the nation?the world?the race?A/ to confront:Religion / Race / PowerB/ The questioning IdentityC/ Involving = HistoryD/ Identity is History being synonyms: being the Present/E/ Attempting to make the past /[?]/

On the back of the sheet, Baldwin begins a new list that focuses on citizenship:

A/ Malcolm’s question:If you are a citizenYou have your civil rightsB/ If you are fighting for your civil rights—what are you?C/ To be a citizen—?

Baldwin spent a lot of time drafting outlines like these. For him, it was a way of searching out new knowledge — especially uncomfortable knowledge.

When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway.5

Baldwin’s Doodles

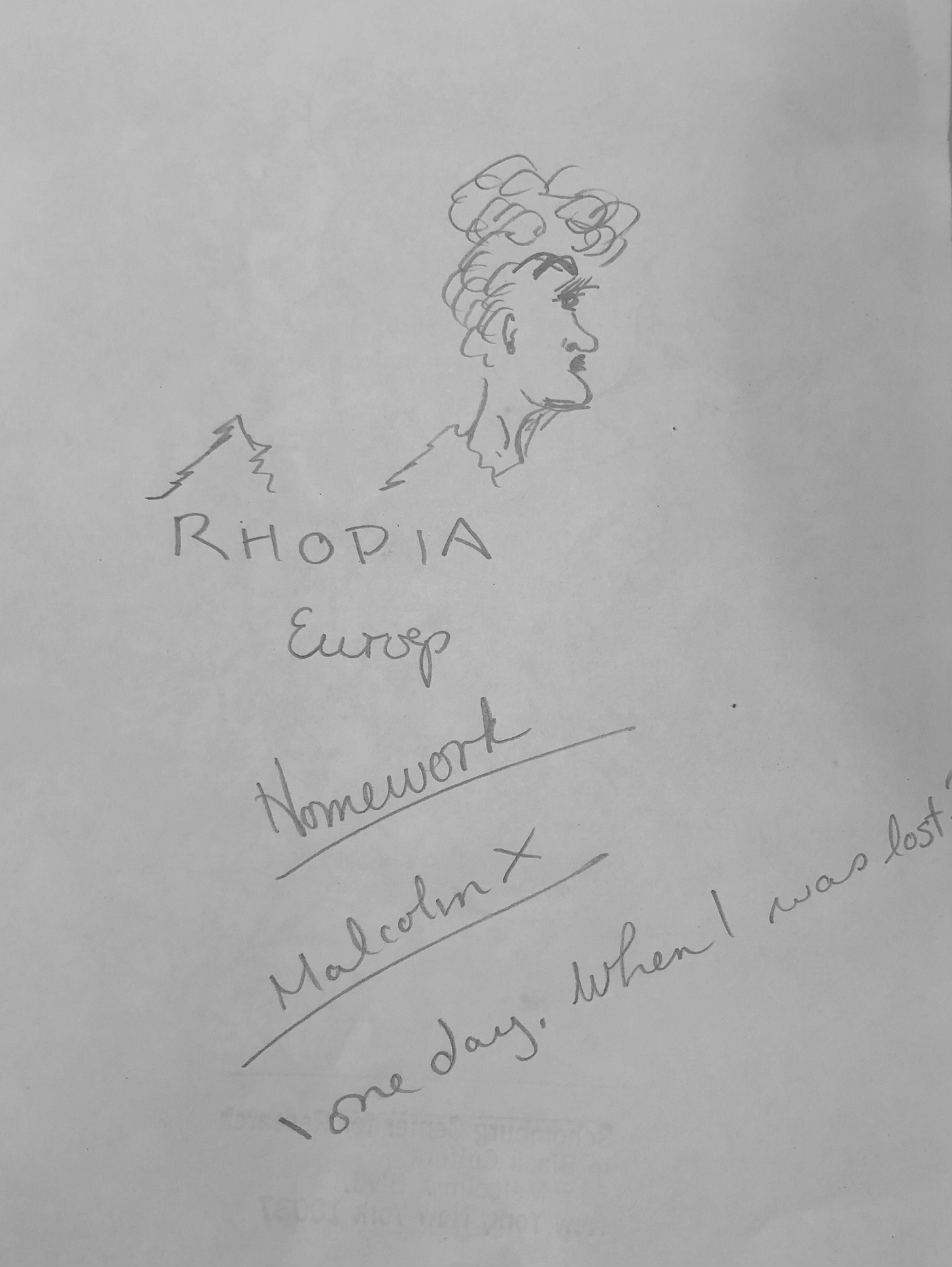

The primary reason I was so disappointed that I couldn’t take photos was because I wanted to share all of Baldwin’s doodles with you. They are all over his notes! Luckily, Yale made parts of their Baldwin collection available online, so I can share some of his sketches with you. Most of the doodles I saw were of women with big eyelashes and messy buns. They look something like this:

From what I saw, Baldwin tended to use legal pads. Some of the legal pads were Rhodia’s “Europ” edition. Rhodia has not changed its style much over the decades:

Baldwin drew faces on many of these notepads’ covers. On one of the Rhodia covers, for example, Baldwin drew a woman’s face in profile (like the image above). But this time he incorporated Rhodia’s logo: one of the trees becomes the woman’s shirt collar. At the risk of embarrassing myself, here is my sketch of what was on the cover of one of the Rhodia notebooks I saw at Schomburg:

Baldwin’s sketch of the lady is significantly better than mine. But you get the picture.

Here is another sketch from Yale’s collection. It includes Micky Mouse on the top and a portrait of a man (perhaps Baldwin himself, with his pronounced widow peak hairline?) on the bottom. In the center, Baldwin has written,

I am a Negro & a native New Yorker

These sketches, combined with Baldwin’s inscription, implicitly ask what it means to be American and Black. In fact, this question occupied much of Baldwin’s writing.

This includes his epic Cambridge debate focused on the question, “Does the American dream come at the expense of the American Negro?” Early in the speech, Baldwin asks his audience to imagine being a young Black boy watching movies and recognizing, for the first time, that you are not white—that you are not the protagonist in the story, but, rather, the villain. Check out this 2-minute clip from Baldwin's 1965 Cambridge debate, in which he says just that:6

Whether we are discussing early Disney’s aggressive whiteness or “Cowboy and Indian” dramas, Baldwin grew up watching entertainment that depicted Americanness as different from—and, often, antithetical to—blackness.

The most exciting thing I saw in Baldwin’s archive were the notes he brought to the lectern for this 1965 debate. But I’ll save that for this week’s postscript.

Notes on Baldwin’s notes:

Doodling was part of Baldwin’s writing practice. In fact, there have been numerous studies that show that doodling improves focus and relieves stress.

Baldwin used anything made of paper as a writing surface. Full of ideas, he would reach for hotel notepads or an Air France sick bag7 when inspiration struck.

Revise, revise, revise! As Baldwin explained:

Rewriting [is] very painful. You know it’s finished when you can’t do anything more to it, though it’s never exactly the way you want it… The hardest thing in the world is simplicity. And the most fearful thing, too. You have to strip yourself of all your disguises, some of which you didn’t know you had. You want to write a sentence as clean as a bone. That is the goal.

If you haven’t already read The Fire Next Time, I hope this post has convinced you to. Any time spent with Baldwin’s writing is time well spent.

Noted is fueled by you. Your ❤️’s and comments inspire me. As always, I would love to know your thoughts. Do you have a favorite line or idea from Baldwin’s writing?

Till Next Week,

Baldwin, James. Interviewed by Jordan Elgrably. The Art of Fiction No. 78. no. 91, 1984. www.theparisreview.org, https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2994/the-art-of-fiction-no-78-james-baldwin.

Leeming, David. James Baldwin: A Biography. Simon and Schuster, 2015, p. 56.

Baldwin, James. “Equal in Paris An Autobiographical Story.” Commentary Magazine, 1 Mar. 1955, https://www.commentary.org/articles/james-baldwin/equal-in-parisan-autobiographical-story/.

The two disagreed on many issues regarding race in America, but they respected one another. Baldwin and Malcolm X debated one another in 1961. You can listen here.

Baldwin, James. The Art of Fiction No. 78. no. 91, 1984.

Buccola, Nicholas. “Appendix.” The Fire Is upon Us, Princeton University Press, 2019.

Schomburg Center, NYPL,Box 35, folder 10.

That opening is the best quote! As clean as a bone. I love that.

Also, I am *fully* behind this writing schedule: "...I hopefully took notebook and fountain pen off to the upstairs room of the [Café de] Flore, where I consumed rather a lot of coffee and, as evening approached, rather a lot of alcohol."

Thanks once again for shining a light on not only aspects of note-taking and notes, but also the person behind them. I leave educated as always, Jillian.

PS your sketch is great!

I love his doodles.

An absolute genius. I saw the documentary in the theatre and it was superb. I’ve been wanting to go to the African American History museum in DC to see his exhibit. There is a lot of his work and pieces from his life in it. I think you’d enjoy it!