Re-Noted: Martin Luther King Jr.'s Organizational Systems

"Every great movement in history has been...carried out through preaching"

In the United States, we are celebrating the life of Martin Luther King, Jr. today—the great civil rights leader and, as it turns out, a remarkable note-taker.

King remains one of history’s most powerful public speakers. And while he certainly had extraordinary natural talent, his training as a preacher gave him the tools to craft powerful speeches that continue to inspire us half a century later.

As just a small example of King’s talent, consider the following selections from a speech King gave to a Philadelphia Junior High School1:

Reading King’s notes, I learned that great public speaking is a matter of significant organization—and significant note-taking. So, let’s look at Martin Luther King Jr.’s systems.

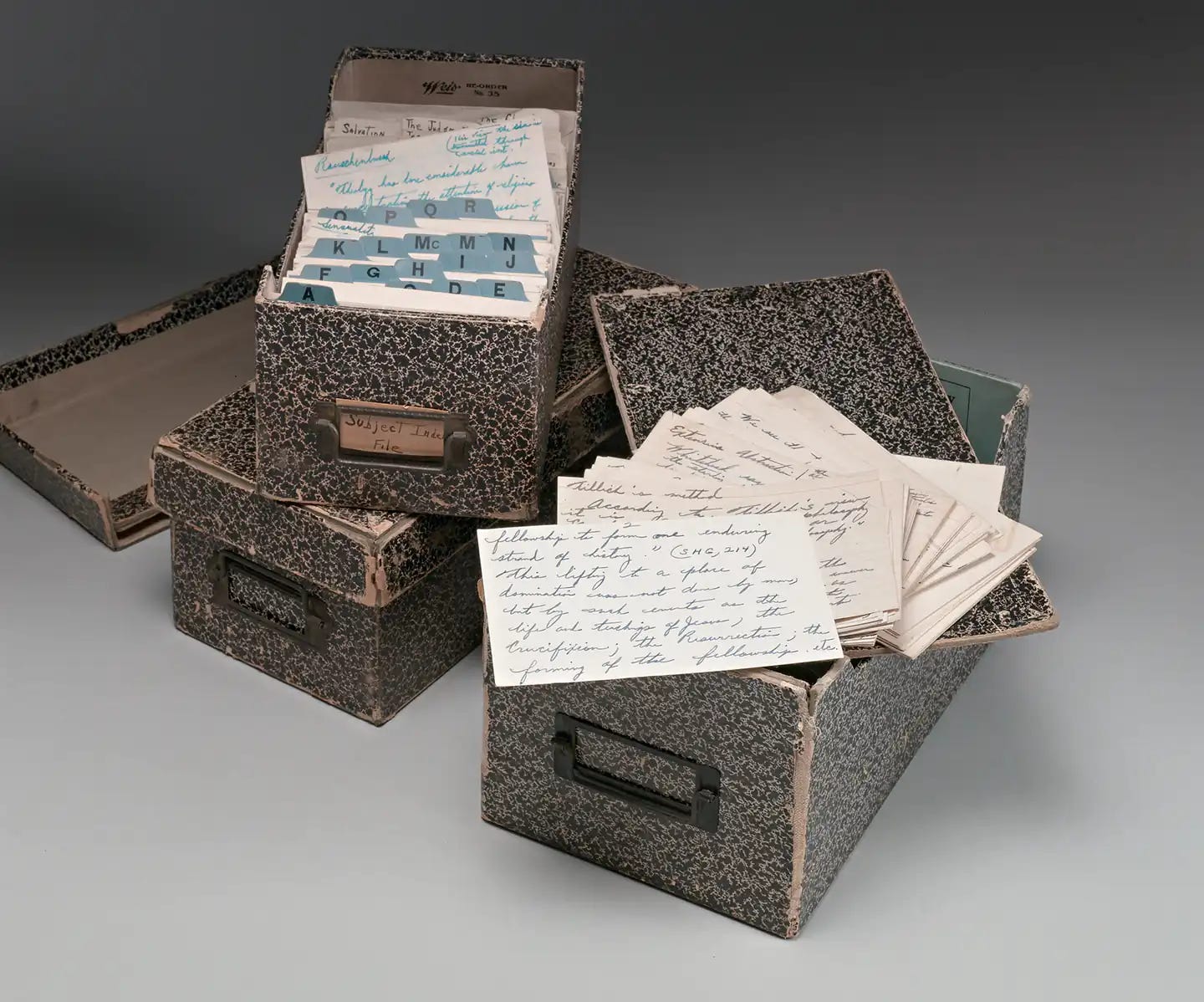

King’s Note Cards

King’s politics were inextricably bound to his religion.2 He served as co-pastor with his father at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta until his assassination. Whether at the pulpit or a rally, King drew from a wealth of source material—the King James Bible, others’ sermons, the many books he read—to inspire his audience.

How did he retain so much material? He used notecards.

Many of King’s notecards come from his time earning a Ph.D. in Systematic Theology at Boston University.

These notecards contain a mixture of quotations from the Bible and religious thinkers as well as King’s personal views. For example, he wrote more than a thousand notecards exploring the Old Testament. Here, he thought deeply about passages that would become cornerstones of his later speeches. By way of illustration, consider one of King’s note cards on the Old Testament’s Book of Amos which includes the lines

But let judgment run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream.

These lines would feature in many of King’s speeches—including his famous “I Have a Dream Speech,” where King said:

…we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

And here are King’s early thoughts on this biblical passage, written in 1953 as a Ph.D. student:

God (Amos)

5:21:24—This passage might be called the key passage of the entire book. It reveals the deep ethical nature of God. God is a God that demands justice rather than sacrifice; righteousness rather than ritual. The most elaborate worship is but an insult to God when offered by those who have no mind to conform to his ethical demands. Certainly this is one of the most noble idea ever uttered by the human mind.

One may raise the question as to whether Amos was against all ritual and sacrifice, i.e. worship. I think not. It seems to me that Amos' concern is the ever-present tendency to make ritual and sacrifice a substitute for ethical living. Unless a man's heart is right, Amos seems to be saying, the external forms of worship mean nothing. God is a God that demands justice and sacrifice

focan never be a substitute for it. Who can disagree with such a notion?3

Notice how King wrote the topic (God) and his source (Amos 5:21:24) at the top of the note card for easy reference.

King’s Annotations (and Plagiarism)

King read widely. Inspired by printed words, he’d often pick up his pen to write in the margins. For example, while training to be a minister at Crozer Theological Seminary, King annotated a textbook with the lines:

Every great movement in history has been prepared for and partly carried out through preaching.

Notice how King copied nearly the exact words in the section he had marked. Indeed, his notecards could be equally problematic insofar as he copied quotes without attribution. This would get him into trouble with his published writings. While King’s talent for absorbing other peoples’ ideas and language served him well as a public speaker, it proved a liability in his written works. His dissertation, for example, included substantial plagiarism. My guess is that it was unintentional and the result of sloppy note-taking practices that did not clearly mark original and borrowed ideas.4

Writing in the margins of his books would be a lifelong practice for King. In fact, he outlined several sermons in his books’ blank spaces. For example, King begins to outline a sermon on pride and egotism after reading about the topic:

King tore this page from the book and deposited it in a folder titled “The Fellow who Stayed Home.” In addition to this outline, King included a draft for a sermon of the same name in the folder.

King’s Folders

From an organizational standpoint, the beauty of sermons is that each revolves around a specific theme. Accordingly, King could devote a single folder to each topic. He accumulated 166 folders, each with a title like “Loving your Enemies” (folder 1), “Why the Christian must Oppose Segregation” (folder 87), “Mental Slavery” (folder 113), and “The Misuse of Prayer” (folder 166). These folders contain King’s outlines; source material, like clippings from books; and drafts.

King gave so many speeches, he often recycled material he had stored in these folders. For example—his most famous speech—the “I have a dream” speech— was not altogether new. He had used the “I have a dream” refrain before. For example, we find similar language in Folder 23: “Negro and the American Dream.” What made King’s 1963 speech in Washington so momentous was that it was the first time the general public heard one of history’s greatest speakers.

I’ll leave you with King’s words:

Notes on King’s Notes

Distinguish between copied and original ideas: The danger in taking notes is that we easily forget what we have merely transcribed vs. what we have created on our own. There are many ways to mark your ideas as different. For example, you could devote the left-hand side of your notebook to your ideas and the right-hand side to transcribed ideas. You could use a color-coding system. Or, you could simply add quotation marks whenever you are copying.

Organize notes by topic: Whether you use notecards, folders, or notebooks, define the topics you use most often. For example, in my teaching files, I have folders for certain lessons (how to write thesis statements, logical fallacies, punctuation, etc.).

Write in your books: Reading is a great prompt for writing. If you’re inspired by what you read, just start writing—even if it’s in the margins of a book.

Noted is fueled by you. Your ❤️’s and comments inspire me. As always, I would love to know your thoughts.

Yours in note-taking,

P.S. Read more about the civil rights movement with my post, “Rosa Parks’s Radical Notes.”

P.P.S. Paid subscribers, look out for more on how King crafted his brilliant speeches later this week.

As King would explain,

In the quiet recesses of my heart, I am fundamentally a clergyman, a Baptist preacher. This is my being and my heritage for I am also the son of a Baptist preacher, the grandson of a Baptist preacher and the great-grandson of a Baptist preacher.

Quoted in King, Martin Luther. The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume I: Called to Serve, January 1929-June 1951. University of California Press, 1992, p.1.

King, Martin Luther. The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume II, p. 165.

King wrote this 1953 note card while studying the Old Testament with his Ph.D. advisor, L. Harold DeWolf.

Here is a summary of the findings of those who worked on collecting and editing King’s papers:

The King Project found no direct evidence that King was aware of any ethical deficiencies in his compositional practices or felt any concern that his compositions might violate academic rules. King's decisions to retain his graduate school papers and to deposit them in an archive at Boston University where they would be available to scholars suggest his lack of conscious guilt or embarrassment regarding his unacknowledged textual appropriations.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers Project. “The Student Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Summary Statement on Research.” The Journal of American History, vol. 78, no. 1, 1991, pp. 23–31.

I've learned so much - another superb post, thank you! Such a fascinating man.

I have a frustratingly large number of quotes - just short phrases, mostly, which I'd jotted down in my daily logs in the past without having noted where I'd come across the words. Overheard in the Village Stores, perhaps? A line from a film? An audiobook? Something Jim's said, maybe. Who knows? And that, of course, is a problem.

I take much more care these days!

It is revealing to see a man portrayed often in very hagiographic terms to have flaws as a scholar.