Last year, I fell in love. That is how it felt to read through Octavia Butler’s papers at the Huntington Library. It’s one thing to respect an author’s published writing, it’s another thing to get to know her intimate experiences of writing those books—how she approached the particular struggles that adhere to a creative life. Reading Butler’s diaries and notes, I got to know her as a person. And I loved everything I learned about her.

By many measures, Octavia Butler (1947-2006) enjoyed a successful career. She was the first science fiction writer to win a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, and she won all of science fiction’s most prestigious awards. However, she would not live to see her greatest aspiration fulfilled. Butler desperately wanted to be on the bestseller’s list, which wouldn’t happen until 2020 (well after her death). She wanted to be a bestselling author, at least in part, to improve her financial situation. Her notebooks are riddled with money worries. She lists items she can pawn (a typewriter, a t.v.) and calculates how much money she has left for food. This is especially heartbreaking because today—with Hulu’s adaptation of Kindred and A/24’s forthcoming adaptation of Parable of the Sower—Butler would have been a very wealthy woman.

Butler was a voracious note-taker. Accordingly there are many threads I could have picked to focus on for this post. The one that I found most compelling was the interplay between these two definitions of success: literary success (being a respected bestselling author) and financial success (buying a house, taking care of her mother).

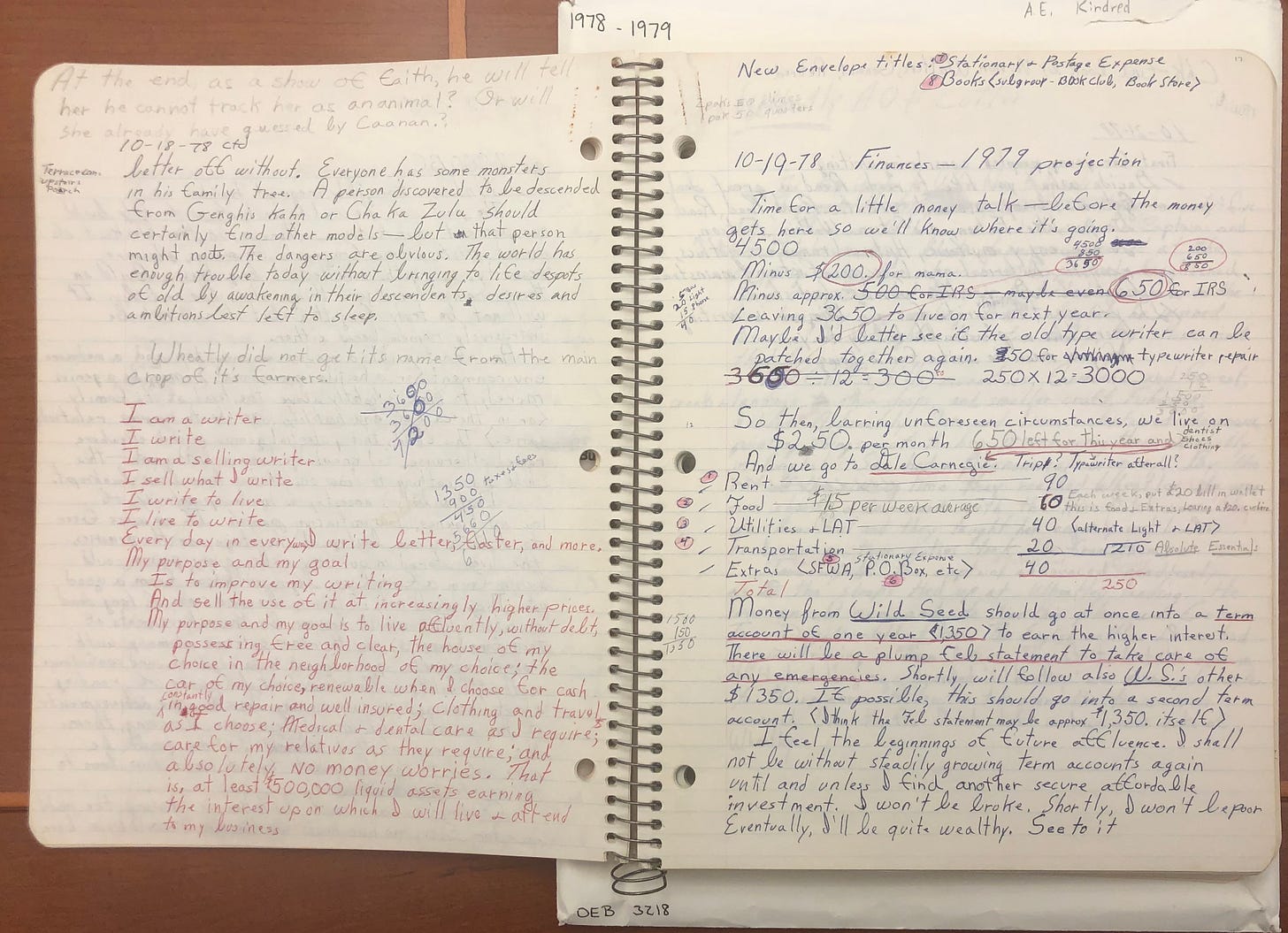

We can see the interplay of Butler’s two definitions of success in the following 1978 notebook spread. On the left-hand side, Butler lists her affirmations (in red ink).

I am a writer

I write

I am a selling writer

I sell what I write

I write to live

I live to write…

On the right-hand side, she calculates her finances after writing a little note to herself:

Time for a little money talk—before the money gets here so we’ll know where it’s going…

This page ends on a hopeful note:

I feel the beginnings of future affluence…Shortly, I won’t be poor. Eventually, I’ll be quite wealthy. See to it.

Butler grew up in a working-class family in Pasadena, California. Her father died when she was young, and her mother made money by cleaning homes. From a young age, Butler struggled with shyness and had trouble making friends. She was always tall (she’d eventually reach 6 feet), which, combined with her deep voice, led to bullying and microaggressions throughout her life. She was, in her words, “slightly dyslexic,” but that didn’t stop her from reading. She felt that public libraries saved her. At the age of ten, she begged her mother to buy a typewriter. By her teenage years, she was submitting short stories for publication.

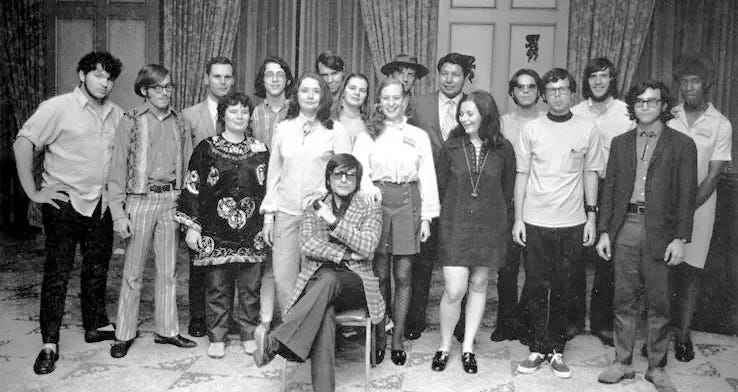

Butler would have to wait until she was 23 for her first stories to be accepted. By that time, she had been encouraged by teachers and enrolled in the Clarion Workshop for science fiction.

35 years later, Butler would be teaching classes for Clarion. Here, she is, in the same far-right position, but now she is surrounded by her students.

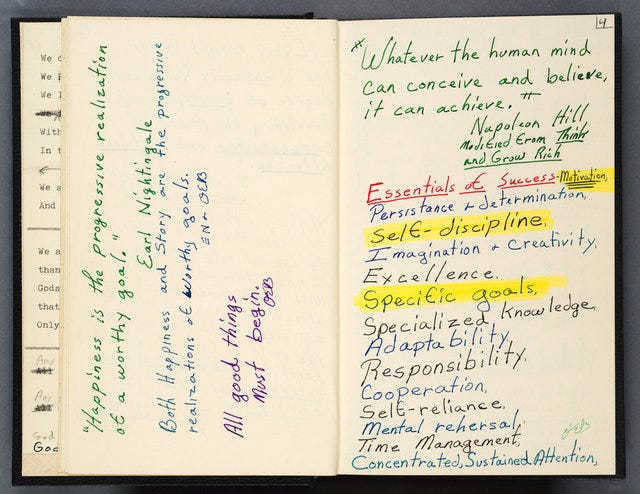

So what are the “essentials of success” according to Butler? She writes them out on the following page:

“Whatever the human mind can conceive and believe, it can achieve.” Napoleon Hill _Think and Grow Rich_1

Essentials of Success - Motivation

Persistence + determination

Self-discipline

Imagination + creativity

Excellence

Specific goals

Specialized knowledge

Adaptability

Responsibility

Cooperation

Self-reliance

Mental rehearsal

Time management

Concentration, Sustained Attention OEB

Let’s consider a few of Butler’s “Essentials for Success,” and how she used her notebooks to stay on track.

Motivation

Perhaps you noticed how Butler included quotations on the left-hand page, opposite her “Essentials for Success.”

“Happiness is the progressive realization of a worthy goal.” Earl Nightingale

Both Happiness and story are the progressive realizations of worthy goals. EN + OEB

All good things must begin. OEB

Earl Nightingale was an inspirational speaker, who Butler likely listened to on audio-books. I love how she built her own inspirational quotation from his—this is the second quote, attributed to “EN + OEB.” You’ll see how Butler refers to herself by her initials (OEB) throughout her notes.

In the early stages of her career, Butler rarely found encouragement from others. As she told Jelani Cobb in 1994:

Do you know who encouraged me?…

Nobody.2

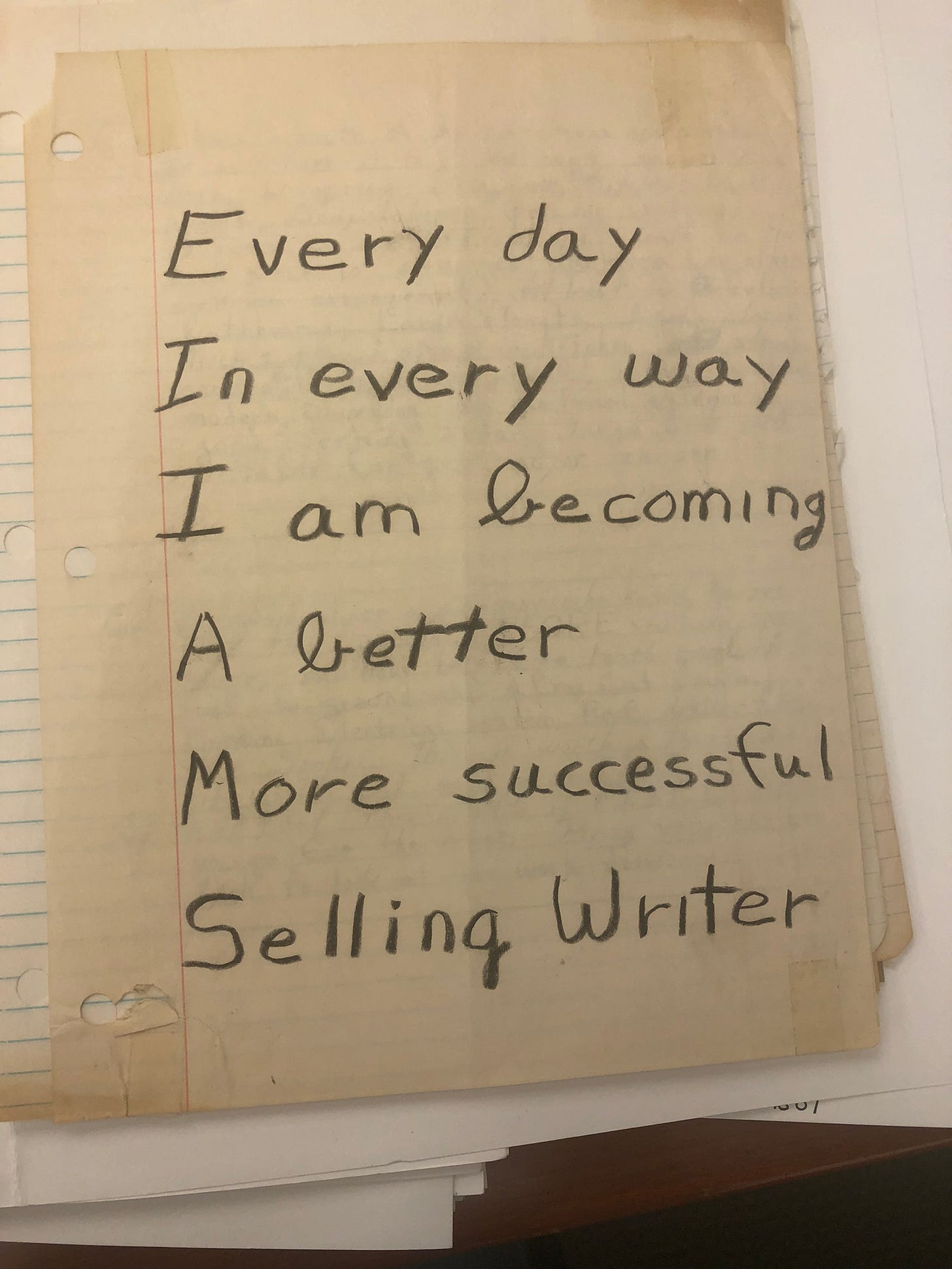

So, Butler penned inspirational notes for herself. In these notes, she reminded herself of her goals and nurtured the budding writer inside of her.

But, perhaps Butler’s greatest motivation was that she felt she would die if she didn’t write. She could not accept the narrow life that awaited her if she gave up writing. The second-to-last reason on the following page, titled “Why do I write,” is the most bone-chilling. Here, she admits that her survival literally depends on writing:

Because I would rather grow and learn and add to myself and writing encourages this.

The only times I have ever considered suicide have been times when I thought I might have to accept the narrowness…Because I don’t think I could stand the narrow, timid person I would be if I did not.

Butler purposefully crossed out that sentence. Notice, too, how in the margin, she reminds herself to “take care.”

I admire Butler’s profound honesty. How many of us truly know what makes our lives worth living?

Persistence + Determination

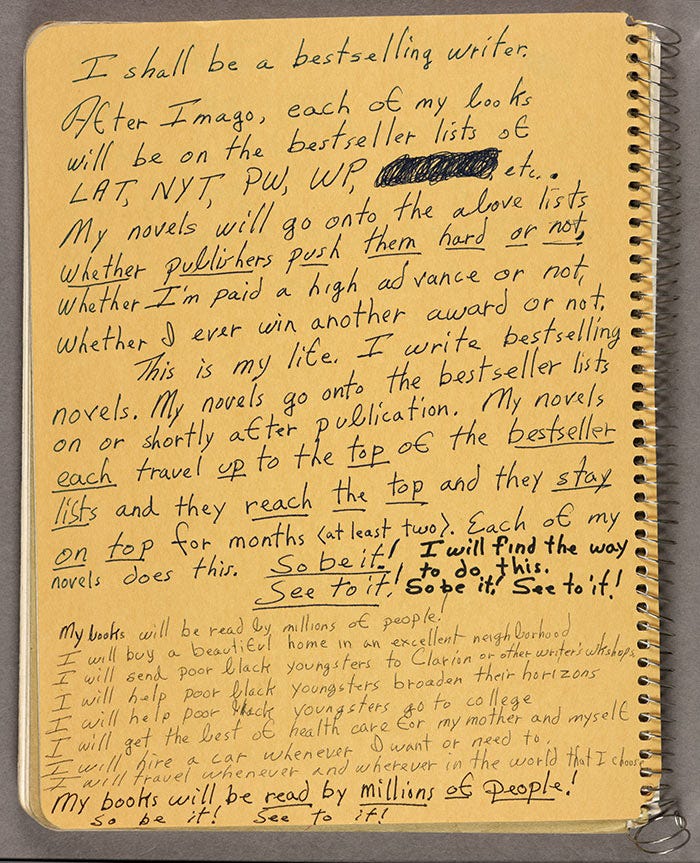

In 1988, Butler was still envisioning her success on the back of a notebook. At the end, Butler writes:

My books will be read by millions of people! So be it! See to it!

Writing, for Butler, was like breathing. So, she needed to find a way to do it. When she was “working for other people”3 as she put it, she’d wake up at 2am to get in her pages. Here, she describes a typical work day (pre- and post- MacArthur Grant).

Of course, the MacArthur Grant (which she won in 1995) would change things considerably for Octavia, but in 1979, she was still struggling to make a living. At this time, she felt she had two strikes against her writing career: she was a science fiction writer (SF as she abbreviated it), and she was a “low seller.” This is why she wrote in her notebook,

…there’s a note on my wall: No less than $5000 for SF, no less than $10,000 for mainstream. I mean it.

The MacArthur Grant effectively solved both of Butler’s problems. As she tells Charlie Rose, the grant did two things for her: the money allowed her to buy a house in a safe neighborhood, and, second, the award’s prestige got people to pay attention to her work.

More awards followed the MacArthur. These included Nebula and Hugo Awards (the highest honors in science fiction), a PEN-lifetime achievement award, and the City College of New York’s Langston Hughes Medal in 2005. Even if she wasn’t on the best-seller’s list (yet), she was admired and widely read.

Imagination & Creativity

Butler fell in love with science fiction because it offered “freedom.” She was limited only by her imagination. And she was a wildly imaginative person. From a young age, she created fantastic stories. Here, she explains her childhood and the first story she wrote about magical horses.

In a notebook from 1958 (when she was 11 years old), she drew these horses. Here’s one example:

Butler’s solitary nature seemed to nurture her creativity. As an adult writer, she literally surrounded herself with the worlds she created: she covered the walls of her office with reminders and maps.

I make signs. The wall next to my desk is covered in signs and maps.4

I didn’t see any maps among Butler’s papers, but I only saw a fraction of her notes—two days was certainly not enough time. I did, however, see many scraps of paper that I imagine Butler must have had hanging on her wall. For example, she wrote notes on-top of her 1976 calendar. I like how some of her appointments are still visible below her very good advice:

Take a character from one Background and set him down in the middle of another, you have your Conflict ready-made.

This note perfectly captures what makes Kindred so wonderful. In this novel, Butler takes a modern Black woman from California (named Dana) and transports her back to a plantation in the antebellum south. Talk about a different context! As Butler reminds herself in another note, so much of Kindred is animated by Dana’s culture shock. Among several other small notes related to Kindred, Butler reminders herself to

Give Dana Trouble!!! Culture Shock!

Self-Discipline

It’s difficult to choose just one example to illustrate Butler’s remarkable self-discipline. In the 1970s, she was making contracts for herself, stating how many pages she would write in a day.

Contract

See to it

This waking period I will do 20 pages MARKET COPY on Psychogenesis.5

Contract See to it OEB

Butler’s contracts exemplify several other essentials of success, especially “Specific Goals” and “Time Management.” Here’s another example of Butler’s successful work habits: it’s a page of “Average Goals” from 1978.

Butler always pushed herself. As she writes, “more is acceptable, possible, and likely.”

Specialized Knowledge

Octavia Butler never stopped learning. She studied the craft of novel-writing and researched the histories and scientific concepts animating her work. To write Kindred, for example, she spent time “at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore and at the Maryland Historical Society.” She also read a lot of slave narratives.6

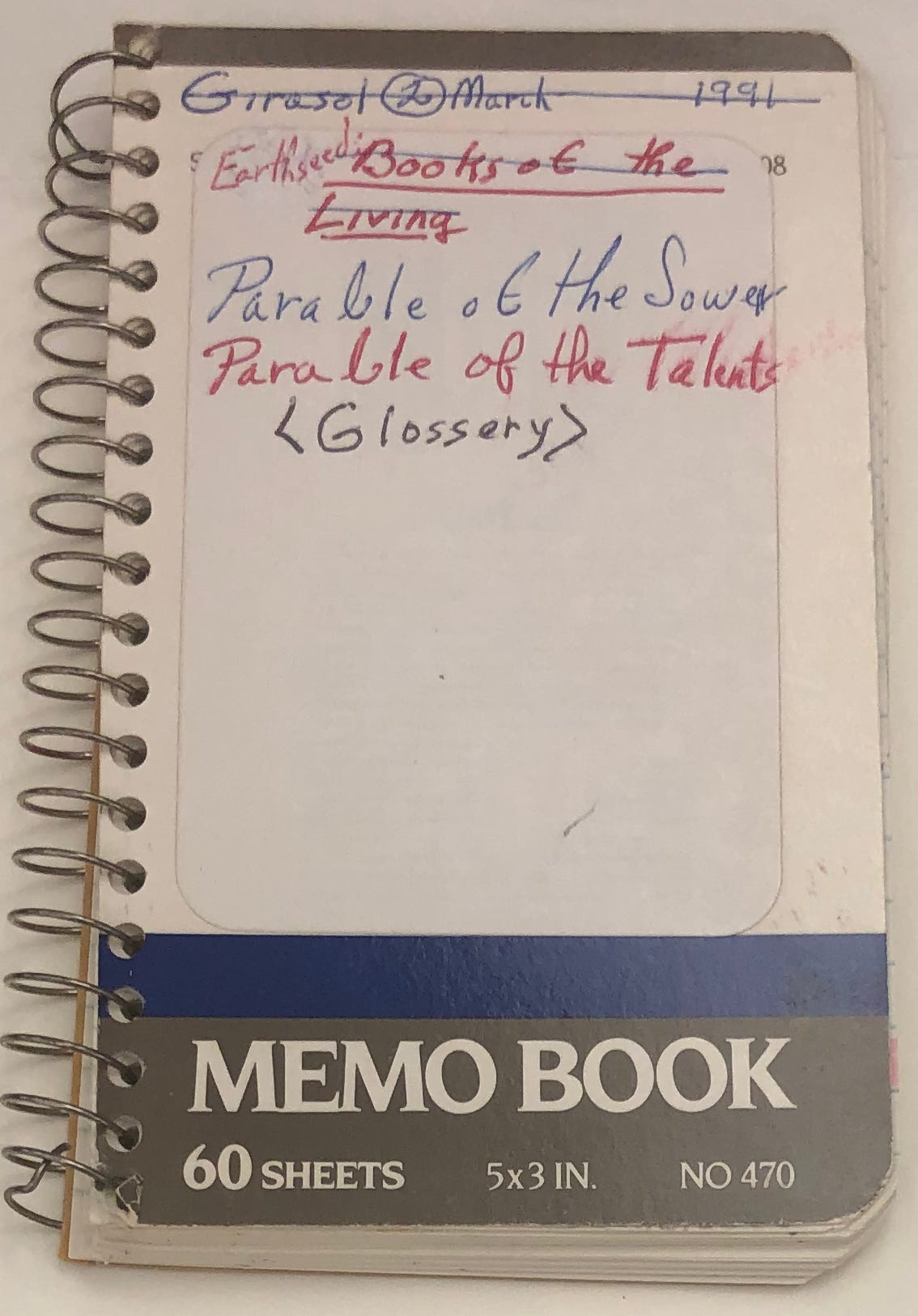

For Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, she created a glossary of words.

Here are her notes on geology, taken from the glossary of Earth and Life Through Time:

Excellence

Butler understood that writing well is only part of the game. While writing came naturally to her, socializing and self-promotion did not. If she was going to become a best-selling author, Butler knew she would need visibility.

On the following page, she coaches herself. First, of course, comes the writing, followed by:

Publicize Yourself

Consciously seize with tenacity every opportunity to get good print publicity

Above all, Butler strove for excellence. For her, this meant publishing deeply researched, socially conscious, entertaining books. Her writing process was incredibly disciplined. Alongside drafts, inspirational notes, and research notes, she also wrote what I’ll call process notes, which she used to reflect on her own writing.

In closing, I’ll add another “element of success” that I observed in Butler’s notes: develop a relationship with oneself. While she didn't publish much about herself, Butler filled her notebooks with reflections on her development as a person and a writer. At the end of a short autobiographical essay, she wrote, “the best and the most interesting part of me is my fiction.”7 That might be true. But, I don’t see how we can separate her fiction from her process. And her process entailed deep, difficult conversations with herself. She pushed herself, she supported herself, and, ultimately, she learned to love herself.

Notes on Butler’s Notes

Write contracts: Butler’s notebooks are filled with pages of these contracts. She signed them and held herself accountable

Motivation: Butler always reminded herself why she was writing

Paper your walls with notes: I love notes in notebooks, but there’s something particularly exciting about notes that are not in notebooks

Write process notes: Butler journaled as she wrote her novels, reminding herself what the story was about and which elements she wanted to highlight

Use Highlighters: Butler would go back over her notes with a highlighter to emphasize important sections

Noted is fueled by you. Your ❤️’s and comments inspire me. As always, I would love to know your thoughts.

Till Monday,

P.S.

Paid subscribers, look out for more on Octavia Butler later this week!

P.P.S

I’ll be on a research trip next week, so there won’t be a post from me. I’m excited to share what I learn when I return!

P.P.P.S

You can read more about Octavia Butler’s notes by reading Lynell George’s excellent study, A Handful of Earth, a Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia Butler.

Butler, Octavia E. Conversations with Octavia Butler. University Press of Mississippi, 2010, p. 50.

Kenan, Randall. “An Interview With Octavia E. Butler.” Callaloo, vol. 14, no. 2, 1991, pp. 495–504. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2931654.

This would become Butler’s second novel, Mind of My Mind (1977), a prequel to her first novel, Pattern Master (1976). The journalist Alex Jung explains that “Psychogenesis had to do with psionics — telepathy, telekinesis, mind control — which was popular in the science fiction she was reading.” See Jung, E. Alex. “The Spectacular Life of Octavia E. Butler.” Vulture, 21 Nov. 2022, https://www.vulture.com/article/octavia-e-butler-profile.html.

Butler, Octavia E. Conversations with Octavia Butler. University Press of Mississippi, 2010, p. 28.

This audiobook I checked out randomly from the library was a delightful and intimate “conversation” between the author and Octavia as she worked through Octavia’s papers at the Huntington Library. Highly recommend: A HANDFUL OF EARTH, A HANDFUL OF SKY: THE LIFE OF OCTAVIA E BUTLER / LYNELL GEORGE.

Love, love, love this. Might copy her notes verbatim into my own notebook. Thanks so much for compiling this.