Re-Noted: Virginia Woolf's Handmade Notebooks

"That’s the real point of my little brown book…that it makes me read —with a pen—following the scent."

After last week’s exploration of the commonplace-book tradition, I realized how much of my own note-taking resembles Virginia Woolf’s (1882-1941). I can’t say that I learned it from her, but I was delighted to find that some of my patterns resemble hers—after all, she’s one of history’s greatest readers. So here’s a glance back to the third post I wrote for Noted—from September 2022. Woolf remains as inspiring as ever!

For Virginia Woolf, one of history’s greatest literary minds, to read was to converse, to hunt, to emulate, to savor. Reading was transcendent. It was a love affair.

She confessed,

Sometimes I think heaven must be one continuous unexhausted reading.1

Best known for her novel Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf was also a prolific essayist, an important publisher, and a lifelong note-taker. For the most part, Woolf took notes while writing non-fiction. She also gathered background information for her novels and other subjects she was studying.

“The great season of reading,” Woolf suggests, “is the season between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four.” To prove her point, Woolf proposes we look at our early notebooks:

Let us take down one of those old notebooks which we have all, at one time or another, had a passion for beginning. Most of the pages are blank, it is true; but at the beginning we shall find a certain number very beautifully covered with a strikingly legible hand-writing. Here we have written down the names of great writers in their order of merit; here we have copied out fine passages from the classics; here are lists of books to be read; and here, most interesting of all, lists of books that have actually been read, as the reader testifies with some youthful vanity by a dash of red ink.2

So let us take down some of Woolf’s notes to see what we can learn from her magnificent collection of 67 notebooks.

Woolf’s Recycled Books

On her 33rd birthday, Virginia and her husband Leonard decided to buy a printing press and start their own publishing house. Hogarth Press was born in 1917 and offered a sanctuary for artists, removed from the pressures of the marketplace. The Woolf’s went on to publish their own works as well as that of their friends. Hogarth has the distinction of publishing the first U.K. edition of T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland.

Virginia had been binding her own books since the age of 19; operating a printing press was an obvious next step. Once the Woolf’s set up their press, Virginia fell in love with the rhythmic work of type setting. She told a friend,

You can’t think how exciting, soothing, ennobling and satisfying it is.3

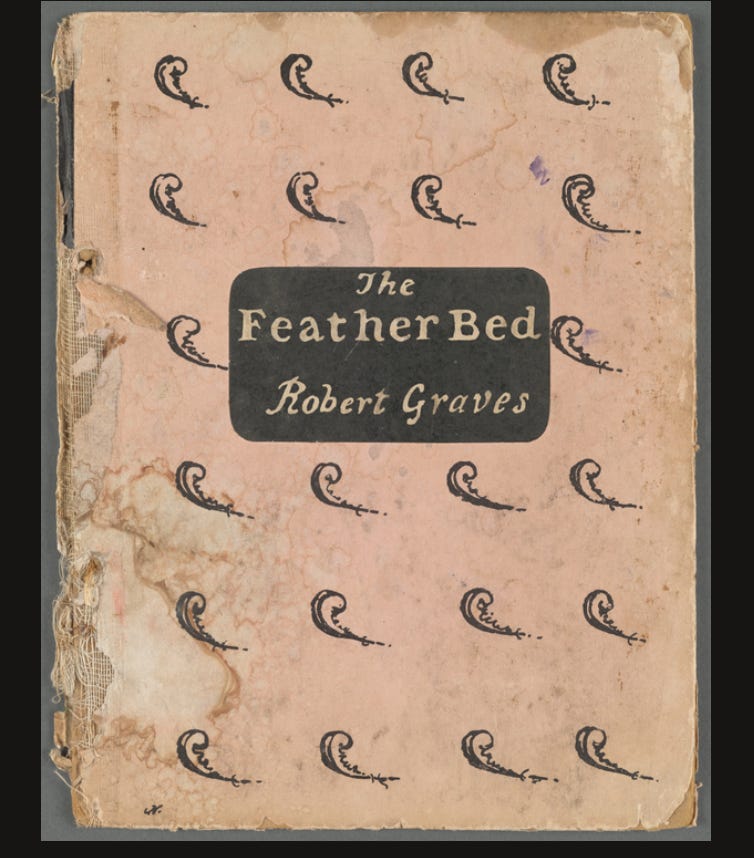

Sometimes, she would make notebooks for herself out of leftover bits from the Hogarth Press’s books, such as this 1929 notebook (notice the purple smudges that match the color of ink she used for part of this notebook):

This particular notebook contains notes on William Cowper and Mary Wollstonecraft in preparation for articles Woolf wrote in the autumn of 1929.

Another notebook, bound with Hogarth Press scraps, covers projects from the 1940s including Robert Fry: A Biography, as well as readings on women and war. Woolf includes several tables of contents throughout, including on the front cover and the spine.

The Agamemnon Notebook

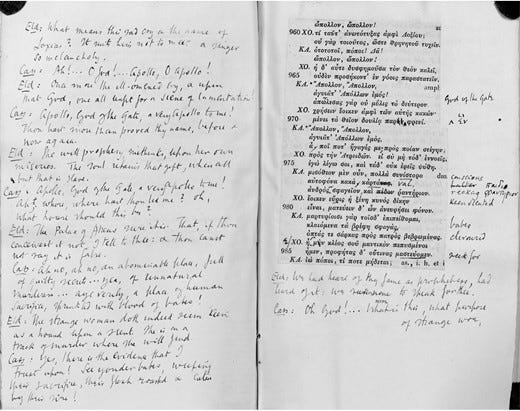

Just as she made her notebooks, Woolf made her own edition of Aeschylus’s play, Agamemnon. She took scissors to a 19th-century edition of the Greek text, pasted the pages into a notebook, and surrounded the cuttings with an English translation and notes. Woolf explains the process:

I am making a complete edition, text, translation & notes of my own – mostly copied from Verrall, but carefully gone into by me.4

Verrall had translated Agamemnon, so Woolf’s edition is not really a translation as much as it is a transcription.5

Woolf’s Colorful Pens

Woolf loved her pens, which she saw as accomplices:

To begin reading with a pen in my hand, discovering, pouncing, thinking of theories, when the ground is new, remains one of my great excitements.6

In 1929 she was writing with gold and green pens. She wrote notes on Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals with a gold pen, which she “didn’t think quite as good as ... [her] old one.”7 But she loved her green pen, which she described in a letter as

…a new lizard green pen, a slippery sort of pen, golden, laxative, loose-tongued8

Woolf’s Indexes

Woolf would create her own index to whatever books she was reading by marking important page numbers and a summary of information to be found there. Often these summaries included quotations or Woolf’s own reflections. She describes this method of reading as though she were on a hunt:

That’s the real point of my little brown book…that it makes me read —with a pen—following the scent.9

She wasn’t just writing out quotations, she was summarizing and analyzing as she read.

Here are a few bits of Woolf’s notes, as far as I can make them out. All of them are on Robinson Crusoe:

53 after the wreck “I never saw them afterwards”…

62 Sudden vividness — an incident—unrelated…

80 The diary repeats everything, as if to make [illegible]…not a cranny for disbelief to enter.

102 being glad I was alive — a mere flight of common joy10

Notes on Woolf’s Notes

Make new notebooks out of old books. Use the cover of an old book and stitch new pages into it

Create your own index to books you read. Record important quotes and observations alongside page numbers.

Cut out sections of a book. This is a bit easier to do in our digital world—you don’t have to take literal scissors to a book when you have ctrl-alt-c.

Noted is fueled by you. Your ❤️’s and comments inspire me. As always, I would love to know your thoughts.

Till Monday,

Woolf, Virginia. The Letters of Virginia Woolf. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975, p.319.

Woolf, Virginia. “Hours in a Library.” Littell’s Living Age, Littell, Son and Company, 1917, p. 281.

Letters II:151.

Woolf, Virginia. The Diary of Virginia Woolf. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1985, II. 215.

This is how the scholar Yopie Prins describes Woolf’s notebook:

Unpublished and unauthorized, her private “edition” was less a translation than a transcription, to which Woolf added a few variations with occasional marks and remarks in the margins, commenting on passages of interest or defining Greek works that she had underlined and looked up in the Greek-English dictionary. After several months of trying “to make out what Aeschylus wrote” (Diary 213) and “master the Agamemnon” (Diary 25), Woolf was pleased to proclaim, “I now know how to read Greek quick (with a crib in one hand) & with pleasure” (Diary 73).

See Prins, Yopie. Ladies’ Greek. Princeton University Press, 2017.

Woolf, Virginia. A Writer’s Diary - Google Books. Harcourt, 1982, p. 147.

Woolf, Holograph Reading Notes, NYPL, Berg Collection, B.11. Cited in Silver, Brenda R. Virginia Woolf’s Reading Notebooks. Princeton University Press, 1983.

Letters, IV, 2025.

Woolf, A Writer’s Diary, p. 301.

NYPL, Berg Collection Holograph Notebook 4.

Oh how I love those quotes of hers about pens! Lizard green and slippery. 😁 🦎

She's so playful, you can feel so much of her personality in so few words.

"That’s the real point of my little brown book…that it makes me read —with a pen—following the scent."

So I've *just* (I know, I know) started actually reading with a pencil and slowing down. It's a completely different experience. I'm annotating so much and enjoying the process. It feels scholarly, in a romantic sort of way. I'm reading Gene Wolfe's Book of the New Sun and the pencil is helping me follow the scent of Gene's incredible depth of writing.

Really enjoying these looks back to the early days of Noted, Jillian. 🤗

Gold and green pens! Lovely!