Re-Noted: Marginalia, or 5 Ways to Write in Your Books

mar·gi·na·li·a /ˌmärjəˈnālyə/ plural noun: marginal notes

As long as there have been books, readers have written in them. These handwritten scribbles in printed books have a name: marginalia. For years, I’ve been thinking about marginalia alongside my friend, and medieval scholar, Dr. Bridget Whearty. She sent me some very cool images of medieval marginalia that I’m excited to share with you. So, here are five different ways to write in books with examples from 1300-2022!

1) Invent Symbols

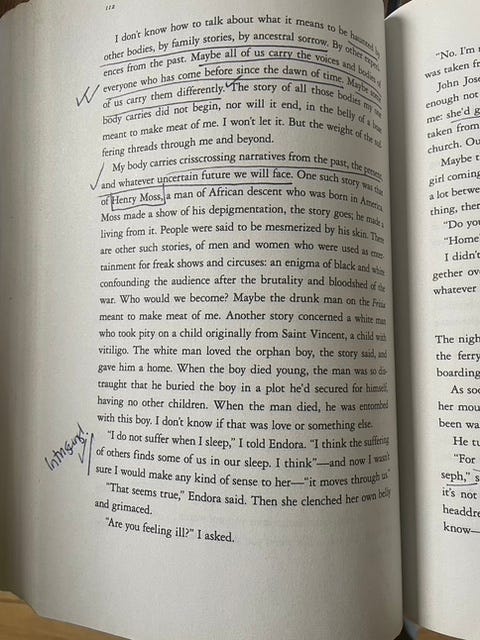

I began thinking about a post on marginalia after I interviewed

about her preparation process for the brilliant interviews she features on . Jane developed an elegant system of note-taking within the pages of a book to support the notes she’ll take later. She explains,I also put checkmarks next to sentences or concepts that pique my interest, but a question hasn’t yet formed. Two checkmarks mean my interest is really piqued, three checkmarks mean my interest is off the charts. A star indicates this is key to the interview even if the question isn’t yet there. Two or three stars mean YES! YES! YES!

Here, Jane prepares for her interview with Lidia Yuknavitch by reading Thrust.

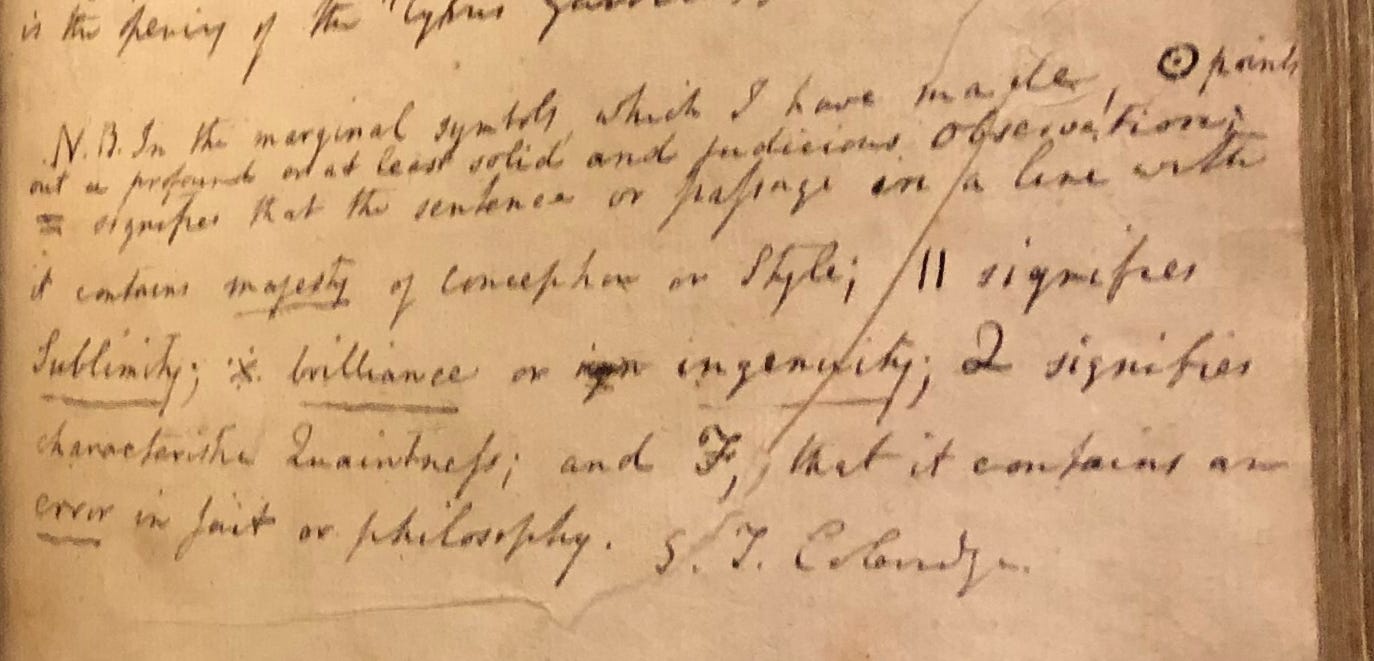

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) is among history’s greatest marginalians—he left behind over 8,000 notes in around 700 volumes.1 It makes sense, then, that he courted women via marginalia. Here, he annotates a text for Sarah Hutchinson. The object of Coleridge’s affection happened to be his best friend’s sister-in-law. Also, Coleridge was married to another Sarah. Definitely don’t take any tips on romance from Coleridge, but if you’d like to borrow his symbols they are as follows:

⦿ points out a profound or at least solid and judicious observation;

= signifies that the sentence or passage in a line with it contains majesty of conception or style;

|| signifies sublimity;

✖︎ brilliance or ingenuity;

Q signifies characteristic quaintness;

F, that it contains an error in fact or philosophy.

And this is what Coleridge’s symbols look like in action:

2. Argue with a Book

Bill Gates is a great reader because he is a great note-taker. He writes in his books as though he were engaged in conversation with the author. He explains,

Taking notes …helps make sure that I am really thinking hard about what is in there.

When he disagrees with the author, Gates will furiously write in the margins. He admits,

it’s actually kind of frustrating...Oh please say something I agree with so I can get through to the end.2

Here is the full 2-minute video:

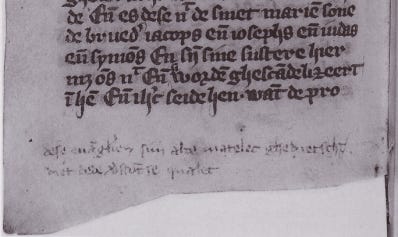

Medieval readers could also be quite combative in the margins of their books. Though, they tended to be much more blunt than I imagine Gates to be. This unknown reader from the 14th century wrote,

Whoever translated these Gospels, did a very poor job

Such direct criticism is probably preferable to the obscene doodles in the margins of other medieval manuscripts.

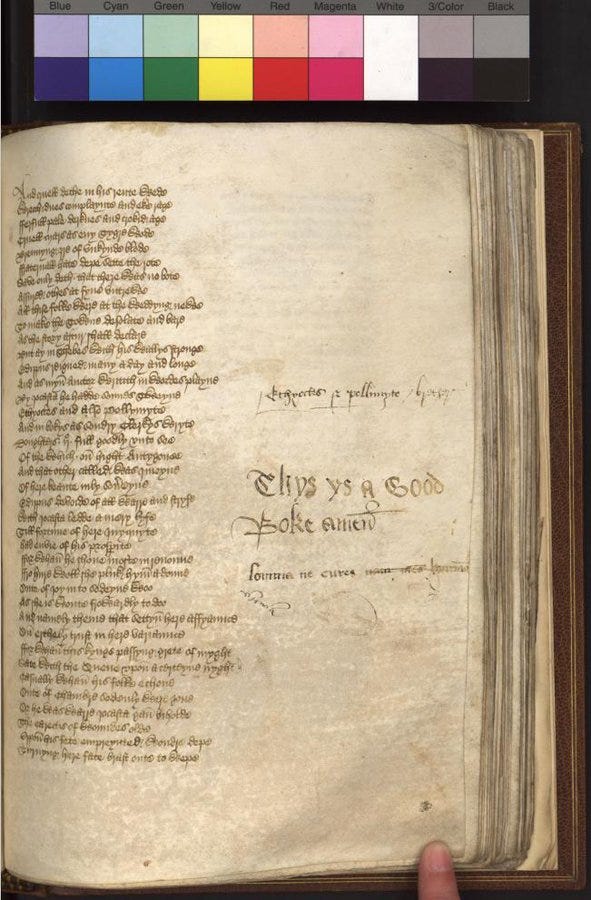

On the other hand, medieval marginalia could be very supportive. Consider the following:

This is a good book, amen

3. Have a Conversation

For Edgar Allen Poe, marginalia was a conversation he had with himself.

In the marginalia … we talk only to ourselves; we therefore talk freshly — boldly — originally — with abandonment — without conceit.3

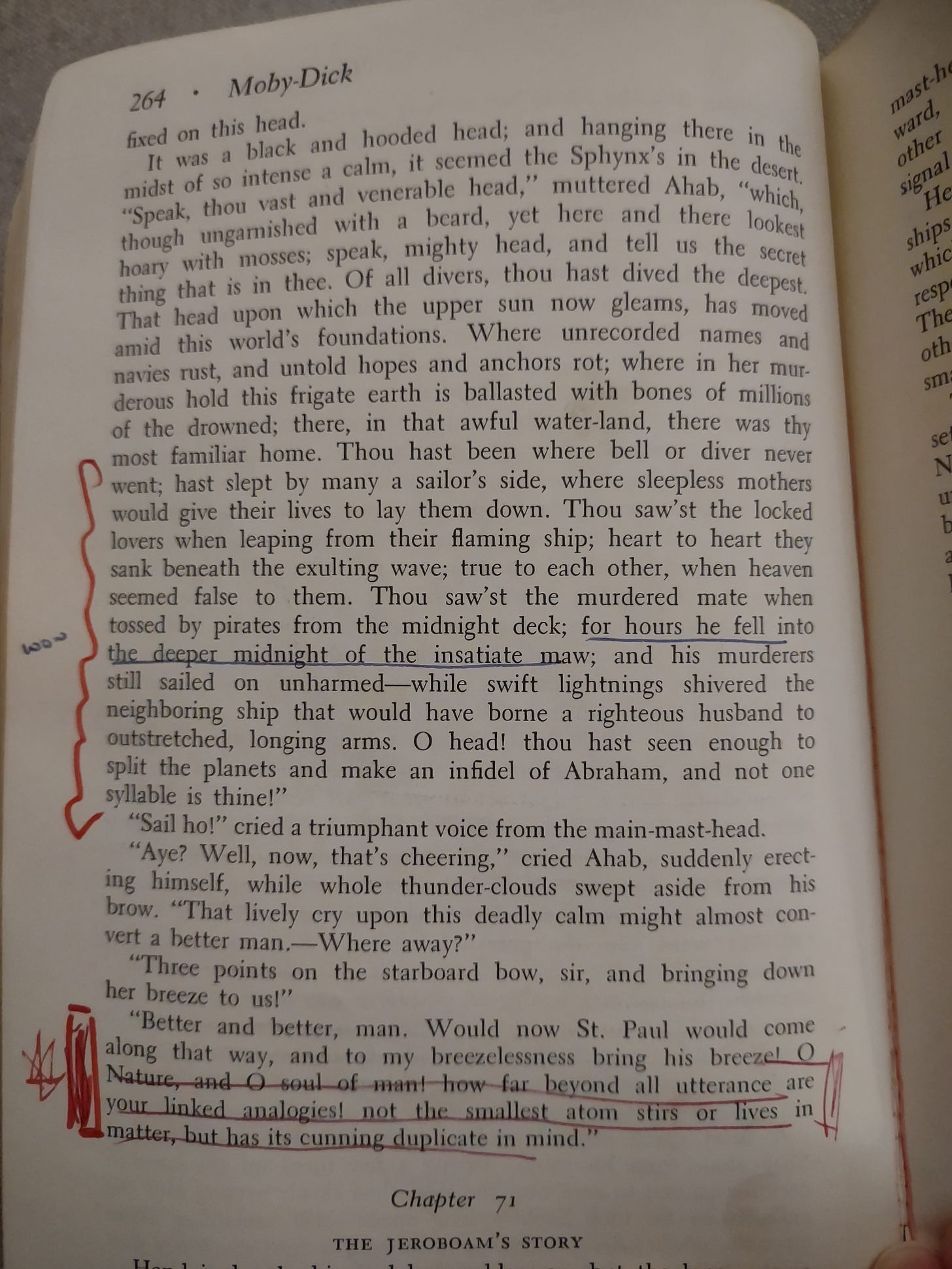

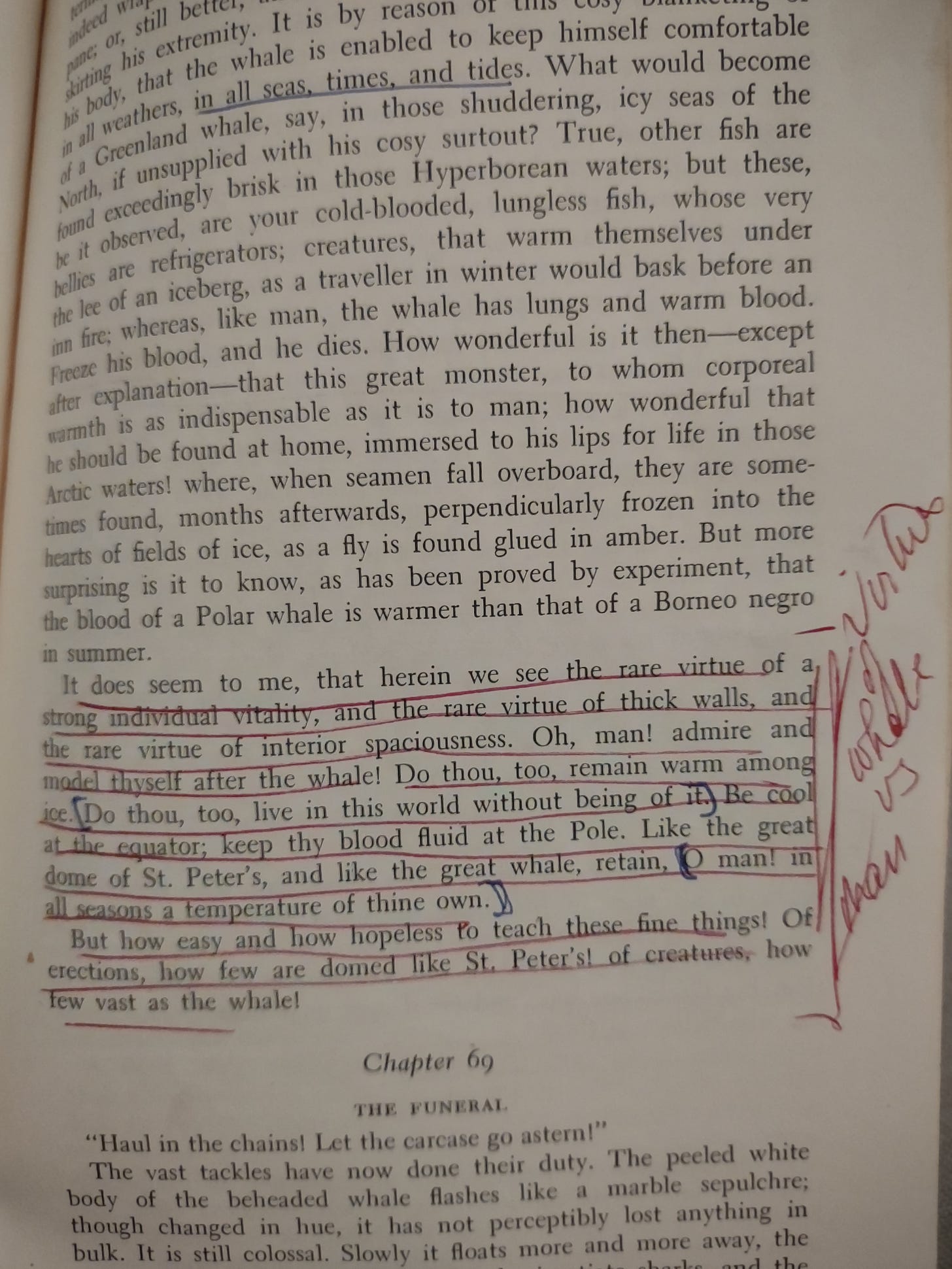

For others, marginalia is a conversation that happens with others and, often, across time. One of Noted’s readers, Taylor Hazan, sent me images from a copy of Moby Dick she inherited when her great-uncle passed away. He had loved this book, covering it in marginalia. Taylor added her own marginalia in blue alongside her great-uncle’s red markings.

Taylor offers this beautiful description:

But my favorite thing about reading the book alongside his notes is that the sections he highlighted meant something to him, so they meant more to me. Even if I didn't find much value in the passages he underlined, they reminded me that everyone reads differently. I especially love the moments when our underlines and checks and hearts overlap: that our breath is taken by the words, even if those breaths happened decades apart and years after his last breath.

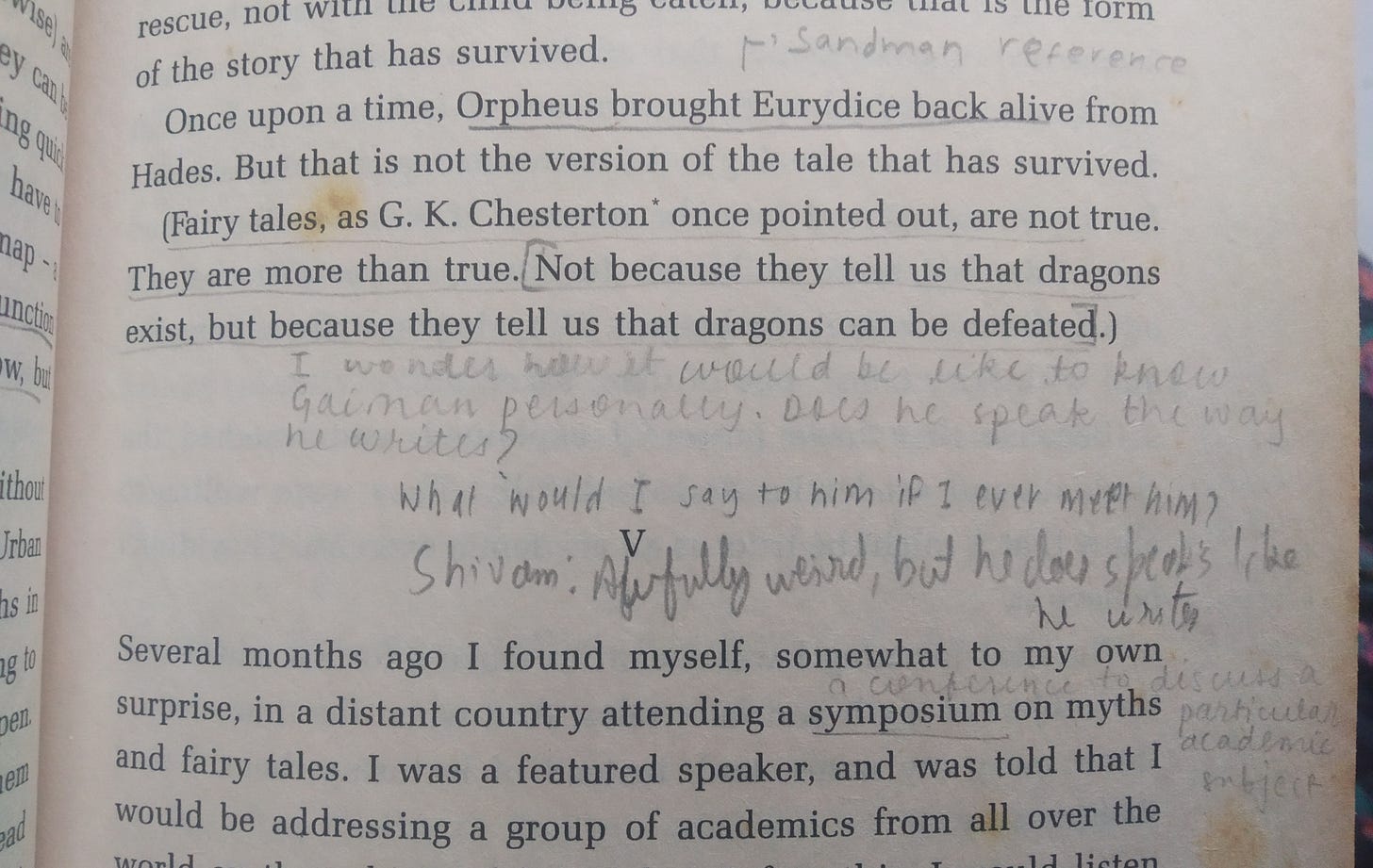

Another reader, Ratika Deshpande, sent images of Neil Gaiman's The View from the Cheap Seats, which she read at age 16. Halfway through reading the book, she agreed to share it with a friend, Shivam; her marginalia changed to include things like, "I think you'll like this description.” Shivam wrote back to her with his own marginalia. And then, Ratika lent the book to a third friend who added more marginalia. Here, the three of them are writing notes to one another:

Ratika transcribes the marginalia for us (and notes that English is not their first language):

On top, the second friend I lent the book to pointing out a Sandman reference

Second annotation, from my first reading: "I wonder how it would be like to know Gaiman personally. Does he speak the way he writes?"

Third annotation, from my second reading: "What would I say to him if I ever met him?" [I still don't know]

Fourth annotation, from Shivam, the first friend I lent it to: "Awfully weird, but he does speaks like he writes."

Fifth annotation, from my first reading, a time when I was still trying to expand my vocabulary by looking things up in the dictionary: "symposium" is underlined. The definition reads: "a conference to discuss a particular academic subject".

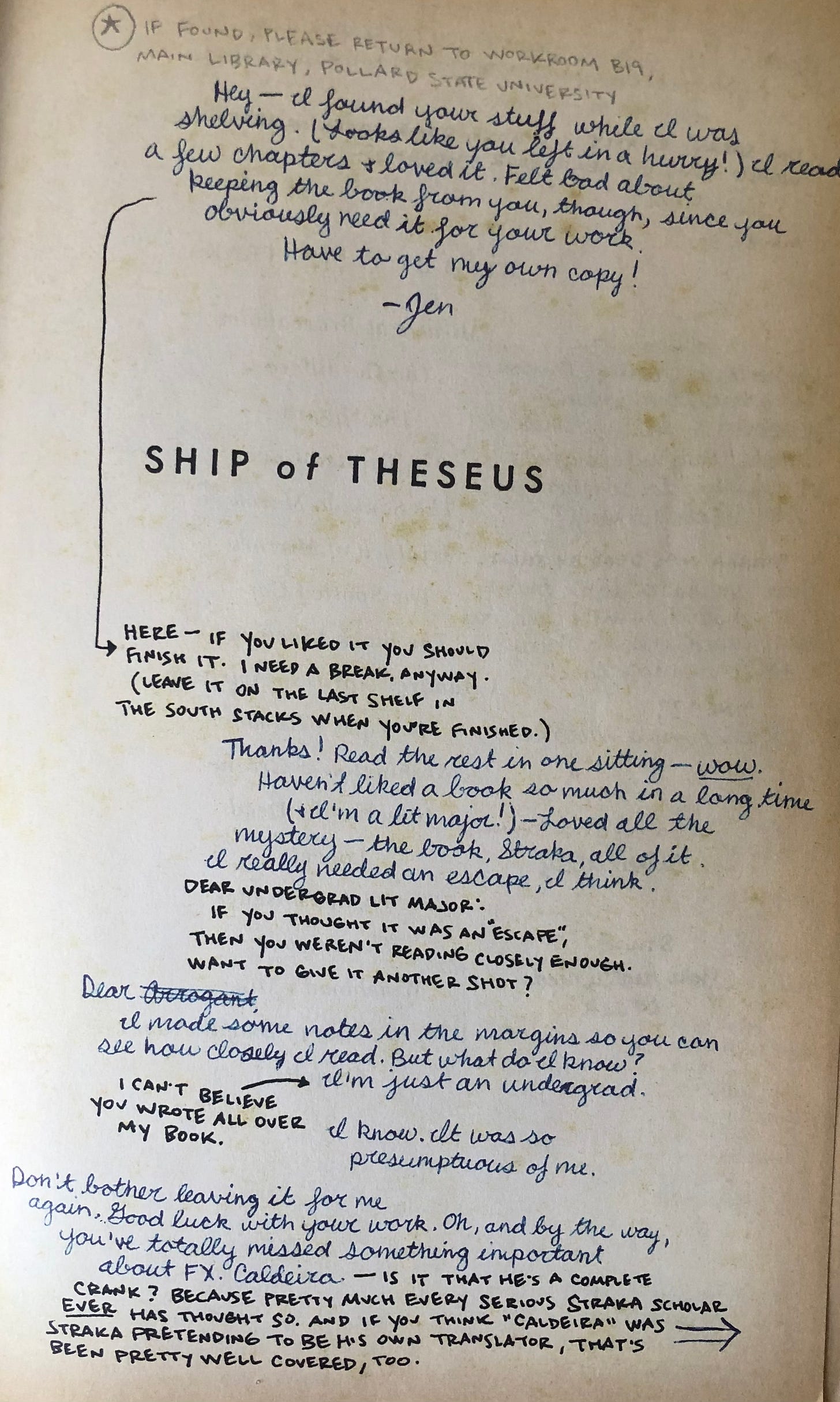

Along these lines, check out S., a novel written by Doug Dorst and J.J. Abrams. A college student finds a novel called The Ship of Theseus. It contains another reader’s marginal notes. So, she enters notes of her own and leaves the book for the stranger. This leads to a fascinating conversation that plays out in the margins of a fictional novel. This is the first page:

The book is filled with notes written on paper napkins, photographs, and postcards. It’s a book that cannot be read digitally:

Many thanks to

, author of the beautifully written , for recommending this book!4. Highlight Important Passages

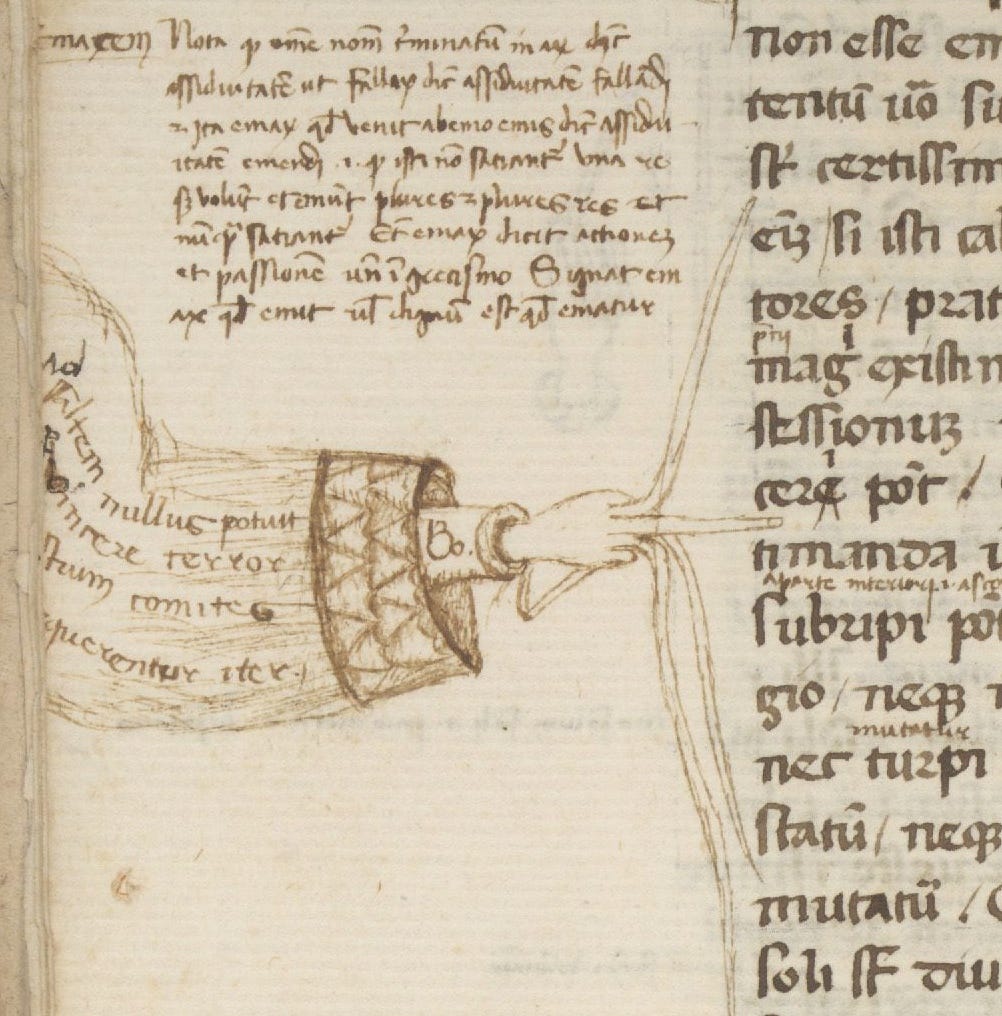

If you’ve been a long-time reader of Noted, you might remember the manicule ☞ (or “little hand”) from Charles Dickens’s marginalia for his performance notes (posted last year). But sometimes one finger wasn’t enough. In the 14th century, a reader used four fingers to mark different parts of a long passage.

On another page, the reader enlisted an octopus’s tentacles:

5. Add to the Text

Pierre de Fermat wrote what is perhaps the most famous example of marginalia. A 17th-century mathematician, Fermat penned extensive marginalia in his copy of Arithmetica. But one note has fascinated mathematicians ever since. Here, he modified Pythagoras’s equation so that it had no solution. Rather than x2+y2=z2, Fermat considered x3+y3=z3. He had “merely changed the power from 2 to 3, the square to a cube, but his new equation apparently had no whole number solutions…”4 And then, frustratingly, Fermat writes:

I have a truly marvelous demonstration of this proposition, which this margin is too narrow to contain.5

Was the margin actually too small? Was there ever a “marvelous proof”? And if Fermat did come up with a proof, what was it? This 300+ year old mystery was finally solved in the 1990s by Professor Andrew Wiles, who came up with a proof for Fermat’s “last equation.” You can learn more about Wiles and Fermat here.

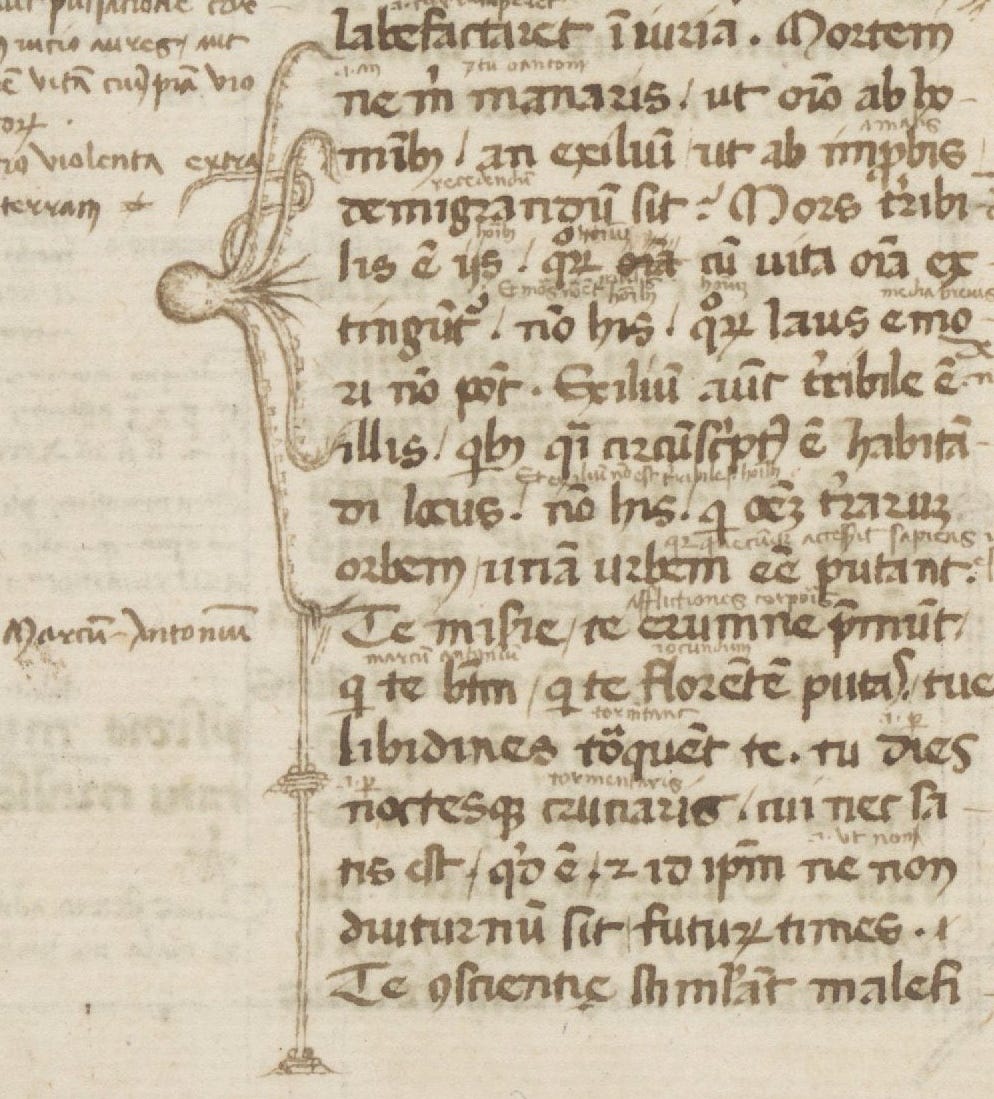

For those less mathematically inclined, there are other ways to add to a text. I’ll leave you with this: a medieval reader added in a doomed duck’s final cry “queck” (or “quack”).

I hope this tour of marginalia has expanded your view of reading with a pen (or pencil) in hand, especially if you are one of those people who rarely, or never, writes in your books.

Noted is fueled by you. Your ❤️’s and comments inspire me. As always, I would love to know your thoughts.

Till Monday,

P.S. Paid subscribers, I’ll be sharing some of my own marginalia later this week!

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Edited by George Whalley. The Collected Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Marginalia I. Princeton University Press, 2001, p. xiii.

How Bill Gates Reads Books. Directed by Quartz, 2017. YouTube.

I got this quote from one of our greatest contemporary marginalians, Maria Popova. Check out her entire site (if you haven’t already), but especially her post on Edgar Allen Poe.

Singh, Simon. Fermat’s Enigma: The Epic Quest to Solve the World’s Greatest Mathematical Problem, Anchor, 1998, p.61.

Singh, Fermat’s Enigma, p.62.

If studying marginalia ISN'T considered a valid, historical field of study, it DEFINITELY SHOULD BE ! I am getting hooked on these witty, interesting, even ENLIGHTING posts.

FORGET ROHRSHACK BLOTS. Seriously, this should be an area of study.

Big fan of marginalia. All my books are full of notes and doodles. (both kinds.)