Stephen Sondheim's Musical Puzzles

"All art—symphonies, architecture, novels—it’s all puzzles...It’s the creation of form out of chaos."

If Oscar Hammerstein had been an astronaut, Stephen Sondheim (1930-2021) would have devoted his life to outer space.1 Instead, Hammerstein was a lyricist—best known for Oklahoma!. Under his mentorship, Sondheim discovered musical theater and embarked on a lifetime of writing lyrics, musical sketches, and puzzle-like drafts.

After his parents’ divorce, Sondheim moved with his mother away from New York City and settled in Bucks County, Pennsylvania—a few miles from the Hammerstein family. Around age ten, Sondheim befriended Jimmy Hammerstein, and through that friendship, Oscar Hammerstein became a surrogate father.

Years later, when the Library of Congress was trying to convince Sondheim to donate his papers, Senior Music Specialist Mark Horowitz brought out Oscar Hammerstein’s handwritten lyrics. The thought of housing his own papers in the same archive as his mentor’s moved Sondheim to tears.

Perhaps you’ve read that the Library of Congress did, in fact, acquire Sondheim’s papers—they became available to the public on July 1st.

As you’ll see, I have more than enough information for a post, but if you’d like me to visit the Library of Congress for a deeper dive into Sondheim’s archives, let me know in the comments!

Sondheim’s Puzzles and Word Play

Sondheim often said that writing a musical felt like solving a giant puzzle. That’s one of the reasons he loved it: each musical note, lyric, and character was a piece to be carefully arranged.

All art—symphonies, architecture, novels—it’s all puzzles. The fitting together of notes, the fitting together of words have by their very nature a puzzle aspect. It’s the creation of form out of chaos.2

And Sondheim famously loved puzzles. He created crossword puzzles for New York Magazine and invited friends to his townhouse for elaborate game nights. He also owned a slew of antique games.

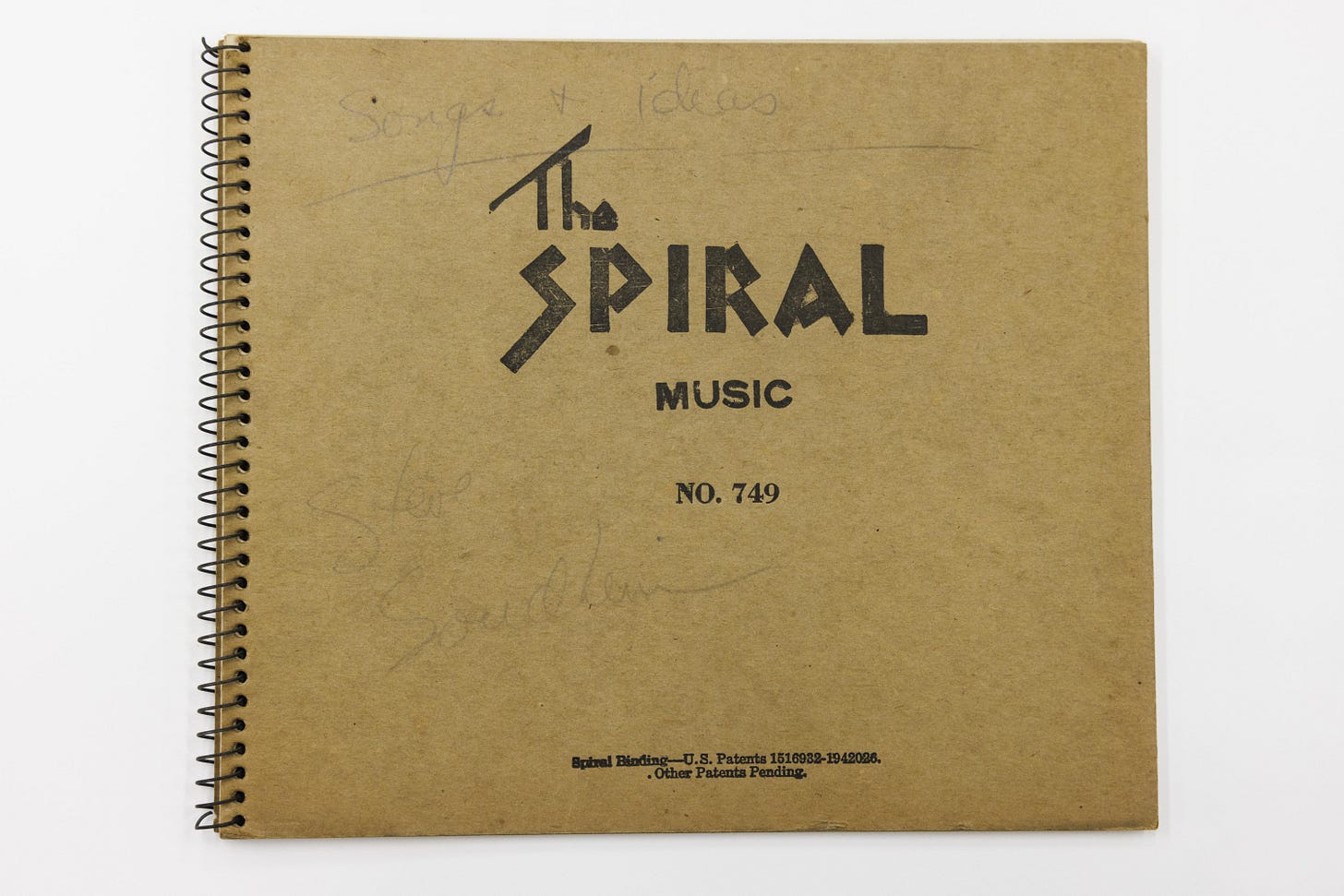

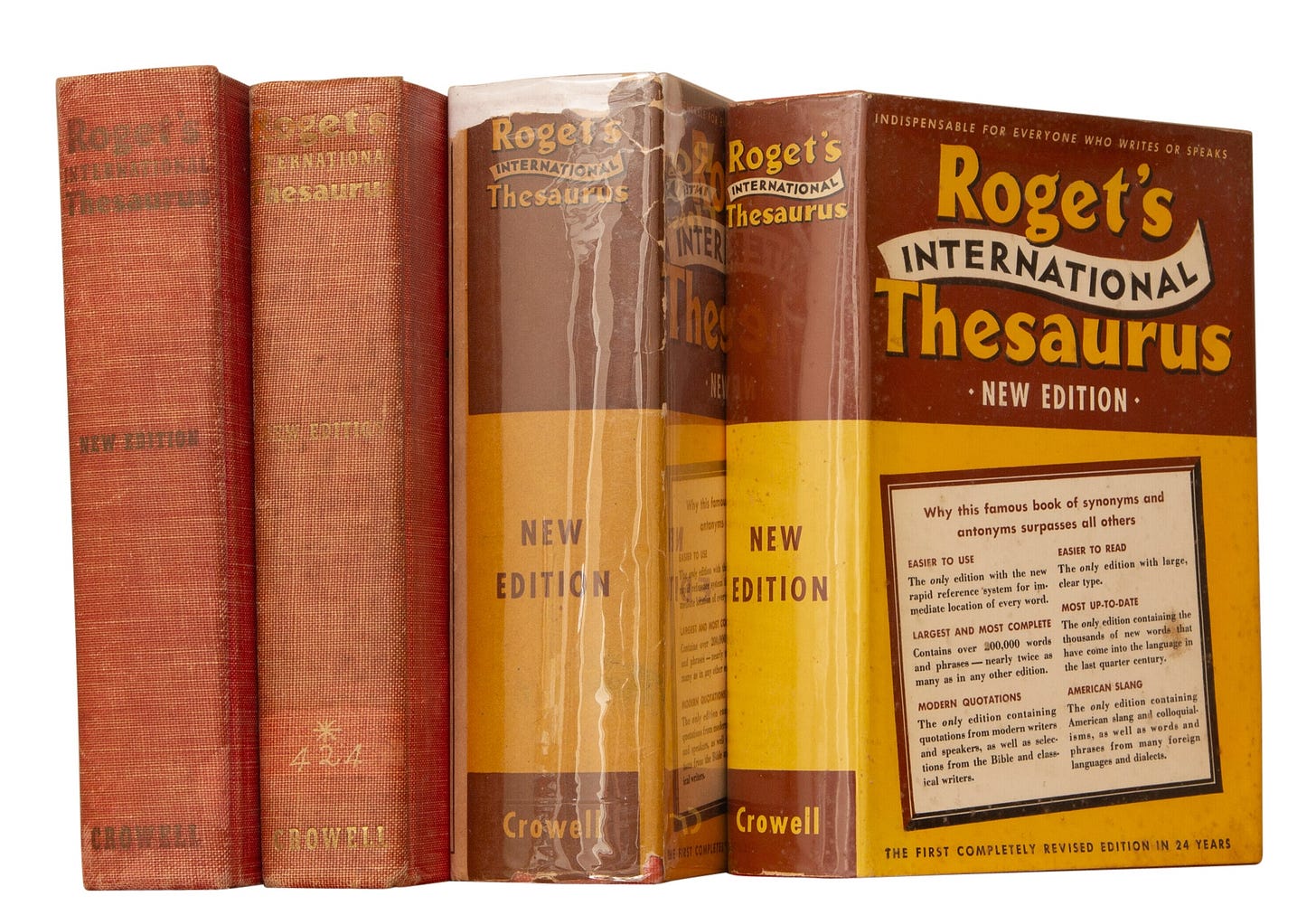

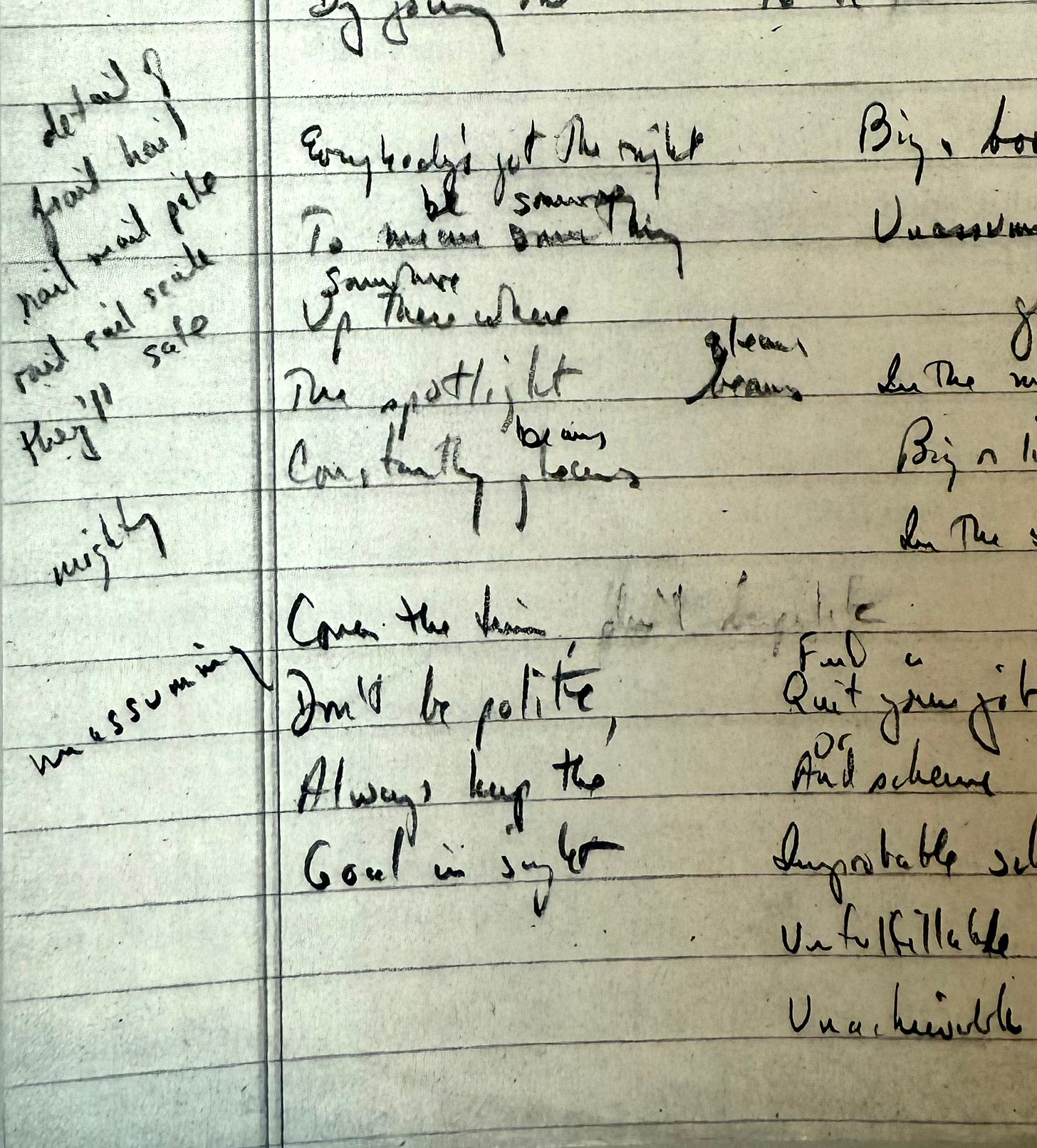

Thus, we find Sondheim playing elaborate word games in his notes—each song was a puzzle for Sondheim to solve. Sondheim filled his notes with lists of words. His early drafts often included multiple rhyme options. He was, after all, looking to surprise his audience. And he felt that the rhymes needed to be perfect—he compared near rhymes to “juggling clumsily.”3 As an assist, he used the Clement Wood’s Rhyming Dictionary and Roget’s Thesaurus.

Sondheim’s word-lists are all over his notes—especially in the margins. For example, while composing the musical Assassins, he noted the following possible rhymes:

detail

frail

hail

nail

rail

they’ll

sale

In addition to rhymes, Sondheim collected words that he associated with a song or character. This might explain some of the other words on the page:

Sondheim’s also listed synonyms in the margins of his drafts. He’d frequently include several options for words—making his lyric sheets as dynamic as Emily Dickinson’s (who also habitually wrote out multiple word choices).

For example, consider this draft of “Tonight, Tonight” from West Side Story:

Today the minutes drag/creep/crawl

The moon is in the/my window

But still the sky is light…

Sondheim claims that “Tonight, Tonight” was especially difficult since the characters lacked psychological depth. He’s right: What do we know about Maria and Tony aside from their mutual attraction? Sondheim’s language in their love songs are vague for this reason. But, in general, Sondheim is not especially proud of the lyrics he wrote for West Side Story. Leonard Bernstein, who wrote the music, pushed him to be more poetic than the young lyricist thought appropriate for the characters. Being young and in awe of Bernstein, Sondheim didn’t yet have the strength to push back.

In case you’re humming4 this song (as I am while writing this sentence), here is a clip from the most recent movie’s version:

Music, according to Sondheim, resembles language. He explains,

And the way you have differences in writing, between singular and plural, you have differences in music between major and minor or between a leading tone and a suspended fourth. But it’s a language you learn—it’s logical—and once you learn it you apply it to the work.5

Accordingly, Sondheim uses a similar technique of playing with possibilities in his musical scores.

Sondheim’s Sketches: Form out of Chaos

All of Sondheim’s works began with what he called “sketches”—musical and lyric drafts. These were short free-association type exercises in which he jots down the feel he’s going for as well as small aspects of character or plot. The sketches also include the specific pattern of chords and bass line he imagines using for the score—unlike most composers, Sondheim added melody later. He explains:

When I write—when I start—if I have an immediate idea, before I start a sketch sheet, I'll put down some kind of basic idea. Where it says "Chopin in C" alludes to how I was imitating Chopin for Fosca's piano piece.6

He also wrote out short meditations on the work and what he expected from it. For example, consider this early sketch of Company:

I have my sketch sheets here. Let me read you some of the notes I put down: "Everybody loves Robert (Bob, Bobby) . . ." the idea of nicknames had already occurred to me. Then I had Robert say, "I've got the best friends in the world," and then the line occurred to me, "You I love and you I love and you and you I love," and then, talking about marriage, "A country I've never been to," and ''Who wants vine covered cottages, marriage is for children." It's all Bob's attitude: "Companion for life, who wants that?" And then he says, "I've got company, love is company, three is company, friends are company," and I started a list of what's company. . . . I started to spin free associations, and . . . the whole notion of short phrases, staccato phrases, occurred to me. By the time I got through just listing general thoughts, I had a smell of the rhythm of the vocal line, so that when I was able to turn to the next page and start expanding it I got into whole lists of things. . . . [W]hat came out of it eventually was the form of that song. . . .7

Here is a full performance of Company, with a star-studded cast and the New York Philharmonic—the first song is “Company,” which begins at around 7 minutes and 37 seconds into the video. Notice the use of nicknames and the way the song starts to define company in all its myriad forms. It is shockingly faithful to the original vision Sondheim recorded in his early sketch.

If you are a music aficionado and a Sondheim fan, I highly recommend the 6.5 hours of interview footage between Mark Horowitz and Stephen Sondheim. Here, the composer goes over his musical notes in great detail. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen anything quite like it—it’s a dream to get to hear someone like Sondheim talk so extensively about his notes and his process.

This is part 1:

Sondheim’s joy and enthusiasm in discussing musical and lyrical problems reveals both the intensity of his passion and the playfulness of creativity that arises when art is seen as a kind of puzzle. His notes provided the space where Sondheim fit all the puzzle pieces together.

Notes on Sondheim’s Notes

Assemble options for yourself: The draft stage is a space for possibilities. So give yourself options: list synonyms, play with different rhymes, free-associate with words.

Creativity is a puzzle: Sondheim said that creating a musical involves producing order out of chaos—solving a puzzle at a very large scale. But Sondheim’s sense of fun derives from his intuition that a song or a musical will work if the parts are arranged correctly. He doesn’t always get it right, but most of the time he arranges the pieces of his musical perfectly.

Start with sketches: Just as Sondheim kept the stakes low with his early drafts by accumulating word choices (rather than forcing himself to make decisions), he also started off with small ideas that allowed him to get a feel for the tone and form of a musical from the very beginning.

Noted is fueled by you. Your ❤️’s and comments inspire me. As always, I would love to know your thoughts.

Yours in note-taking,

P.S. Paid subscribers, look out for more on Sondheim and his tips on creativity later this week!

P.P.S. If you enjoyed this post, you might also like my essay on Bernstein.

Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story Notes

In the last year of his life, Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) traveled to Berlin as the wall came down. To honor German reunification, Bernstein led an orchestra of musicians from East and West Germany through Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. You can watch it here:

Sondheim describes his relationship with Hammerstein in this way in many interviews, including those in Stephen Sondheim in His Own Words, BBC Audio, 2013.

Quoted in Schiff, Stephen. “How Stephen Sondheim Puts It Together, The New Yorker, 28 Feb. 1993.

Sondheim, Stephen. 2011. Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group., p. xvii

Sondheim’s thoughts on a song’s “hummability” are fascinating. People originally complained that West Side Story’s songs weren’t “hummable.” But, as Sondheim points out, hummability is a function of repeated listening. Once West Side Story became a film with a huge budget for promotion so that disc jockeys starting playing the music, the songs suddenly became hummable.

He says: “Anything that’s hummable immediately is something you’ve hummed before.” Quoted in Schiff, Stephen. “How Stephen Sondheim Puts It Together”.

Quoted in Gottfried, Martin. Sondheim. Harry N. Abrams, 2000, p. 36.

“Conversation with Stephen Sondheim, Part 2.” Video. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Quoted in Gordon, Joanne Lesley. Art Isn’t Easy : The Achievement of Stephen Sondheim. Southern Illinois University Press, 1990, p. 45.

I was at the 1985 performance of "Follies". I still cry when I listen to the opening number.

Thanks for posting this. I loved it. Take a deeper dive, please!