The Brontës' Scribble Mania

"…scarcely one chapter had escaped a pen-and-ink commentary."

You’d be forgiven for thinking Wuthering Heights is a great love story if you only experienced it as a film.

If, however, you read Wuthering Heights—Emily Brontë’s novel—you will know that it is something else entirely: haunting, gruesome, and terribly violent—I can’t imagine a more dysfunctional and unsatisfying romance than the one shared by Brontë’s Catherine and Heathcliff. Perhaps that is why filmmakers continue to transform the wild novel into a more familiar love story.

As we await the release of the newest adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights on Valentine’s Day (a movie that seems to skew more towards fan fiction than faithful adaptation), let’s take a look at the imaginative notes the Brontë siblings left behind.

The Brontës’ Miniature Books

Emily Brontë died at 30, never having experienced a romance of her own (as far as we know). However, she was a skilled storyteller, having spent her entire life co-authoring adventures with her siblings—Charlotte (author of Jane Eyre), Anne (author of the less-well-known Agnes Grey) and their brother Branwell, a poet who painted himself into and then out of the following family portrait.

The Brontës’ illustrious writing career began in the summer of 1826 when their father returned from a trip bearing gifts: a dancing doll for Anne (6 years old), a toy village for Emily (7 years old), a set of ninepins for Charlotte (10 years old), and a set of toy soldiers for Branwell (8 years old).

By the next morning, each Brontë child had selected one of Branwell’s toy soldiers and named it: Charlotte named her soldier after the Duke of Wellington and Branwell, cheekily, named his after Wellington’s rival, Napoleon.1

Then the siblings wrote plays and stories that featured these toy soldiers.

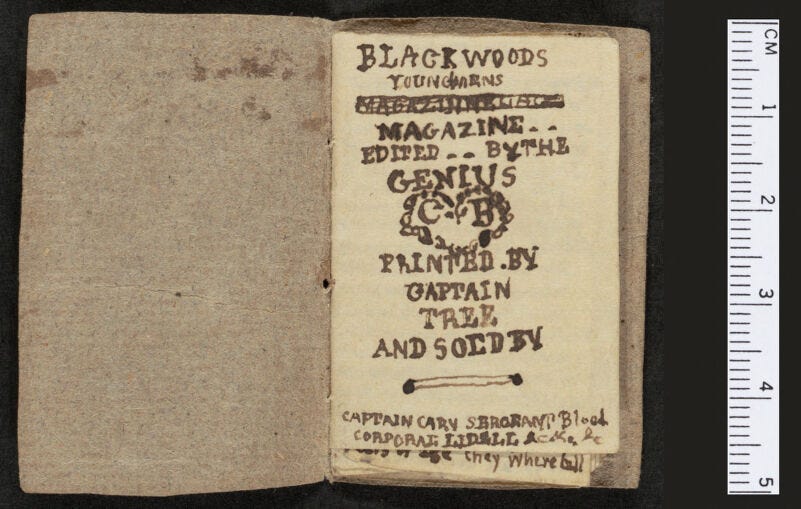

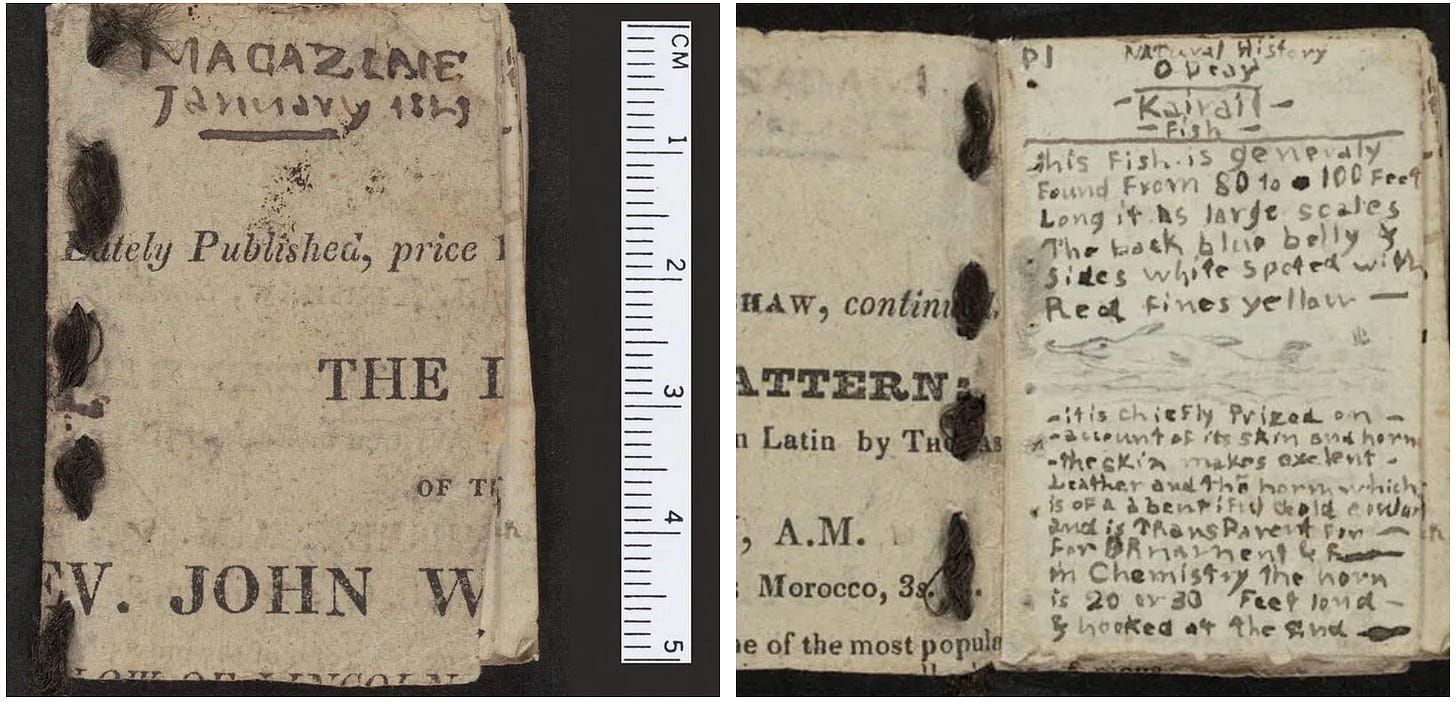

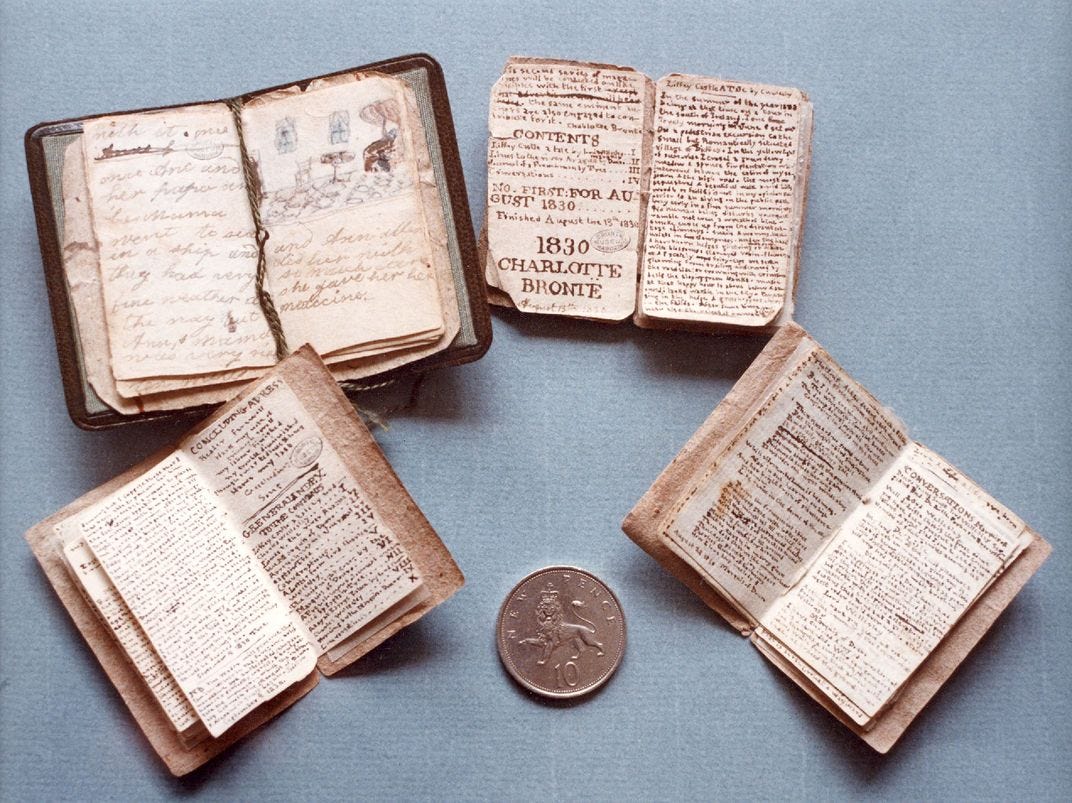

Sized in proportion to the toys, the children’s books were minuscule, pictured here with a 10-pence coin for scale.

Imagining their books as part of the printed world, the children designed clever title pages and dedications.

The following book, modeled off of the popular Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, claims as its editor

the genius C B [Charlotte Brontë]

The siblings used whatever paper was at hand as covers—bags of sugar, wallpaper, or newsprint. Here Branwell repurposed an advertisement:

Imagining themselves as published authors was all part of the make-believe.

While the two eldest siblings, Charlotte and Branwell, created their imaginary world of Angria, the younger siblings, Emily and Anne created Gondal.

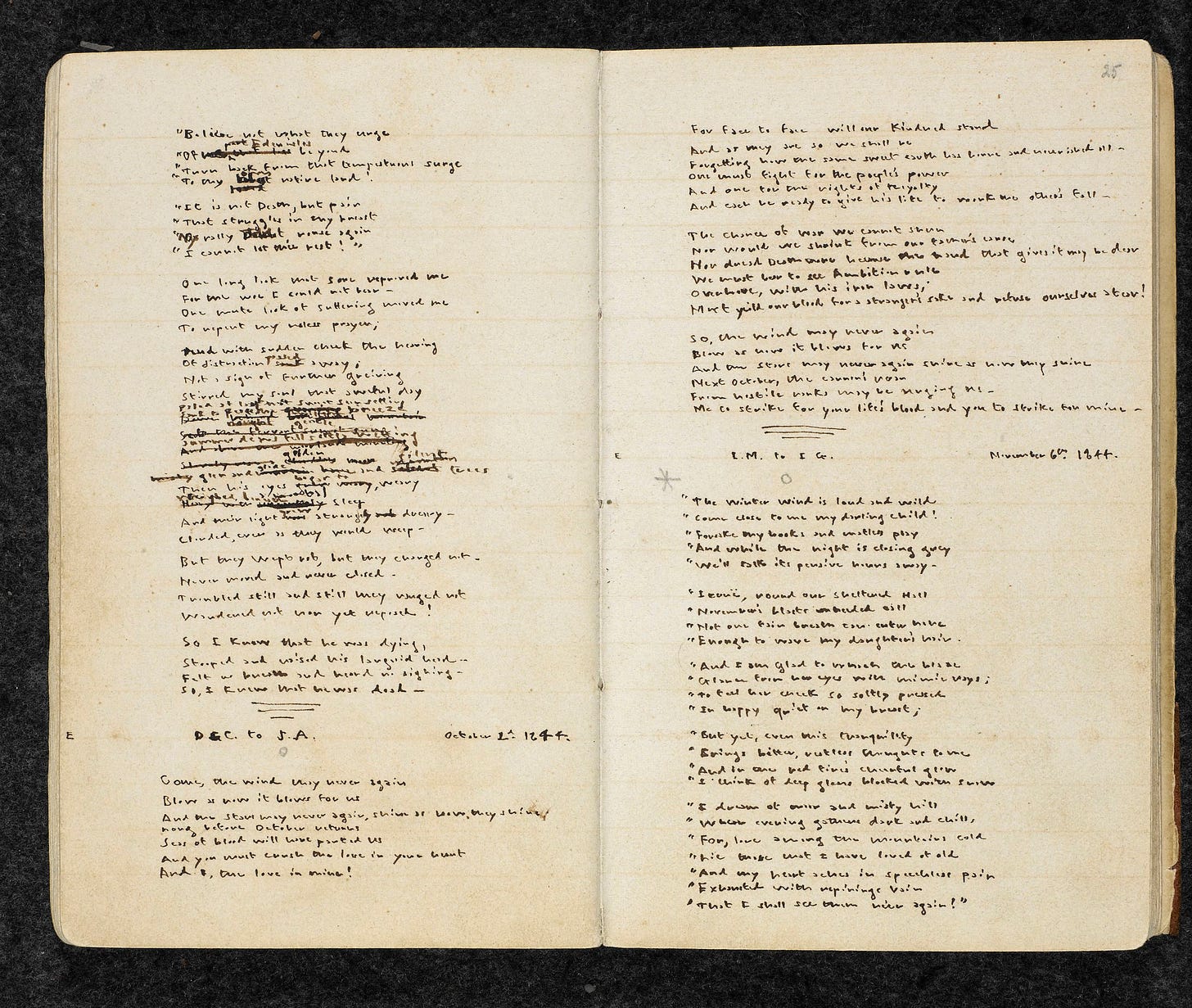

Later, Emily would copy out many of her poems for Gondal in a new, full-sized bound notebook.

For Emily, this act of writing and recopying, moving words among scraps of paper was part of her process—but more on that in next week’s postscript.

The Brontës’ Marginalia

In Wuthering Heights, we meet Catherine through her books—particularly the way she wrote all over them. Our narrator describes how

…scarcely one chapter had escaped a pen-and-ink commentary—at least the appearance of one—covering every morsel of blank that the printer had left. Some were detached sentences; other parts took the form of a regular diary, scrawled in an unformed, childish hand. At the top of an extra page (quite a treasure, probably, when first lighted on) I was greatly amused to behold an excellent caricature of my friend Joseph,—rudely, yet powerfully sketched. An immediate interest kindled within me for the unknown Catherine, and I began forthwith to decipher her faded hieroglyphics.2

This description was likely taken from life, as the Brontë siblings made a habit of covering their books in writing. And often this writing took the form of a diary, unrelated to the actual content of the book.3

For example, Charlotte complains of homesickness on an empty page of her copy of Russell’s General Atlas of Modern Geography, writing:

Brussels—Saturday morning Oct. 12th 1843—First Class—I am very cold—there is no fire—I wish I were at home With Papa—Branwell Emily—Anne and Tabby—I am tired of being among foreigners it is a dreary life—especially as there is only one person in this house worthy of being liked—also another who seems a rosy sugar-plum but I know her to be coloured chalk.4

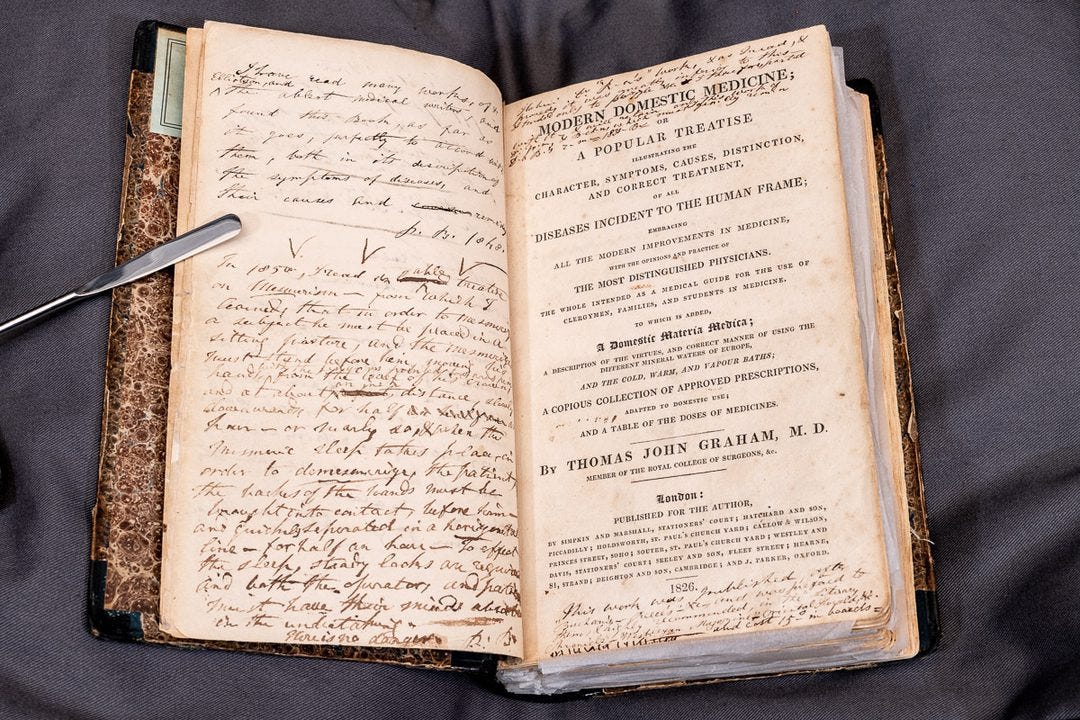

In another example, their father, Patrick, covered a medical book with his observation on the maladies affecting the family:

I have read many books of experiments, and medical writings,

and have observed much in the course of my own practice…In 1805, I found the alkaline treatment or alkalinism — from reading & conversing then I was led to the more careful & minute examination

of the state of the pulse in a strong posture, and the immediate effect of posture upon it…

Printed books, it would seem, were just another source of paper for the Brontës. And they went through a lot of paper.

The Brontës’ Scraps

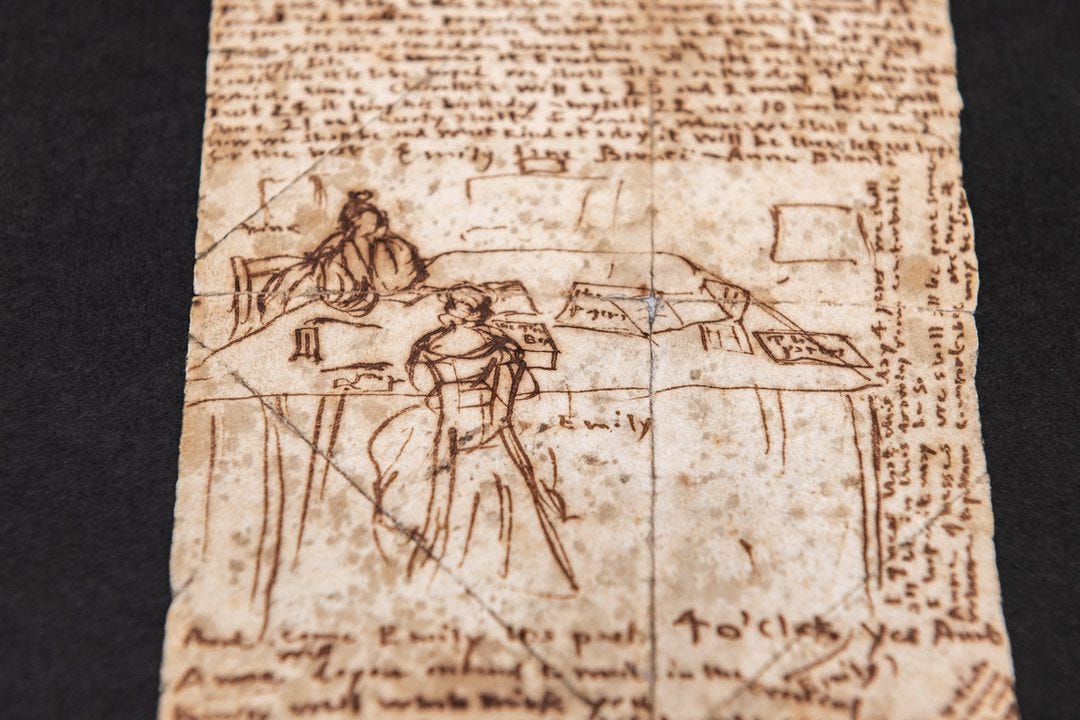

The siblings were always writing—any scrap of paper, no matter how small or paltry would soon be covered in tiny script.

Mostly, the siblings wrote together at the dining-room table, pictured here in a sketch Emily drew of herself and Anne.

The siblings referred to this compulsion to write as “scribble mania.” Charlotte, taking a break while teaching, writes that

[Branwell] might indeed talk of scribble mania if he were to see me just now, encompassed by [students]…all wondering why I write with my eyes shut—staring, gaping—hang their astonishment.5

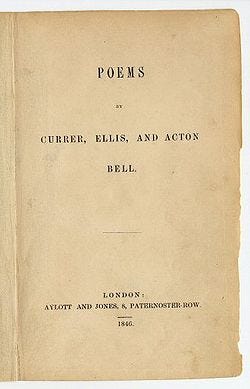

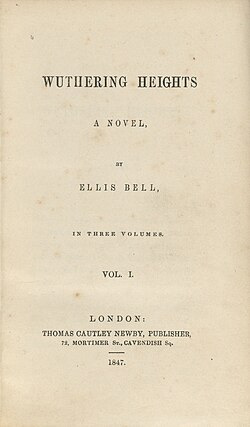

All the scribbling paid off when the Brontë sisters first made it into print with a collection of poetry. It was here that they claimed their pseudonyms: Currer (Charlotte), Ellis (Emily), and Acton (Anne) Bell.

Encouraged by this success, they sent off their novels. Though the last to be accepted, Jane Eyre was the first to be published (October 1847). It quickly became a bestseller.

A month later, in November 1847, Emily’s Wuthering Heights was published in three volumes—the third volume, however, was Anne’s Agnes Grey.

Nineteenth-century critics hated Wuthering Heights, offended by what they considered its rudeness and amorality. The critics weren’t wrong—it is a rude and amoral novel, but that’s what readers have come to love most about it.

The siblings died in quick succession soon after—Emily and Branwell died in 1848 and Anne in 1849, all from tuberculosis. Ultimately, only Charlotte remained to oversee her sisters’ legacies. She was the only sibling to marry, yet she died in 1855, barely a year into her marriage, likely from complications during pregnancy.

This week, as I reread Wuthering Heights, listened to Kate Bush on repeat, and wrote this post, my thoughts returned again and again to a small watercolor illustration in the New York Public Library’s collection of Emily Brontë’s papers.

It is a delicate slip of paper, with a simple request:

Forget me not

Of course, we have not forgotten Emily. How could we? I daresay, the way we think of memory—its rhythms and recurrences—is indelibly marked by that most haunting of novels, Wuthering Heights.

Notes on the Brontës’ Notes

Creativity is a form of play: We need only look at children to see how fun creativity can be. I’m amazed by how many of our most talented authors started honing their craft as children making playful magazines.

Write in your books: The idea that we should keep our books free from writing is a thoroughly modern idea. For avid writers like the Brontës, blank spaces in books offered another scrap of writing space.

Write (and walk) Together: Writing was rarely solitary for the Brontës—even if it was sometimes secretive. The siblings gathered around the dining-room table to write. Often getting up to walk around it while they read their works aloud. The habit was so ingrained that even when Charlotte was the only sibling left, she continued walking around the table alone.6

Wuthering Heights was the first adult novel I read in a single sitting—I was 15 and utterly transfixed. I’d love to hear about your first experience reading Wuthering Heights in the comments.

Yours in Note-Taking,

P.S.

Paid Subscribers, look out for a deeper dive into Emily’s notes next week.

Described by Carol Bock in “‘Our Plays’: The Brontë Juvenalia.” The Cambridge Companion to the Brontës, edited by Heather Glen, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 35.

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. Penguin Classics, 2003, p. 20.

See Lutz, Deborah. The Brontë Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects. W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Quoted in Ratchford, Fannie Elizabeth. The Brontës’ Web of Childhood. New York: Columbia University Press, 1941, p.160.

Quoted in Bock,“‘Our Plays’: The Brontë Juvenalia.”

Drawing from Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte, Juliet Barker writes:

The sisters wrote their books in close collaboration, reading passages aloud to each other and discussing the handling of their plots and their characters as they walked round and round the dining-room table each evening.

Barker, Juliet. The Brontes. Little, Brown Book Group, 2010.

I don't rememner when I first read "Wuthering Heights", I just remember that it was in translation (decades later I did read the original, and was amazed once again at the genius of the translator), and I must have been quite young.

I do remember reading"Jane Eyre" first, and I loved it, and re-read it numerous times too, but "Wuthering Heights"...I was completely transfixed, and it's not a book that someone..grows out of, so to say.

Its staying power is comparable with all the best books ever written, and it's a part of my "take 30 books you love the most" when moving across the globe.

I'm very attached to our very old edition, that falls apart, so at certain point I bought a newer one, with the unsatisfying cover (covers are frankly oddly important. to yours truly. especially for the books one met early and felt in love).

I did find a comprehensive website once, of some "Wuthering Heights" fan, who also dedicated a page to a glossary (Joseph's speech used throughout the book)...I'm very grateful to this person, because later it was much easier to read the original.

This fan shared my opinion that a good cinema adaptation to the book doesn't exist yet, even though he did range and rate them from very bad to better ones.

I do think that Kate Bush, in four minutes, does a job thousand times better than any of the adaptations. I also can listen to it on the loop.

(it was a funny moment though, in Mona Awad's "Bunny", when the heroine, wary of some new surroundings, and the song blasting there, thinks "wuthering, wuthering, wuthering heights, how long is this song anyways":)

I did see the limited series on Bronte's family, "Walking Invisible" I think. I still can't really understand how they managed to write so brilliantly, and especially it boggles the mind that Emily, who hardly left their house, wrote "Wuthering Heights".

My edition does contain some of her poetry too.

Thank you for this excellent post, Jillian- I knew the kids in the family were highly creative, yet you illustrate it perfectly.

Wow, did not know about these miniature books. Wonderful detail on the sisters, Jillian. I love reading about long-dead writers, even famous ones! Now when I re-read these classics, I'll be picturing them as little girls getting started with their writing careers. Lovely images.